Sutanu Guru

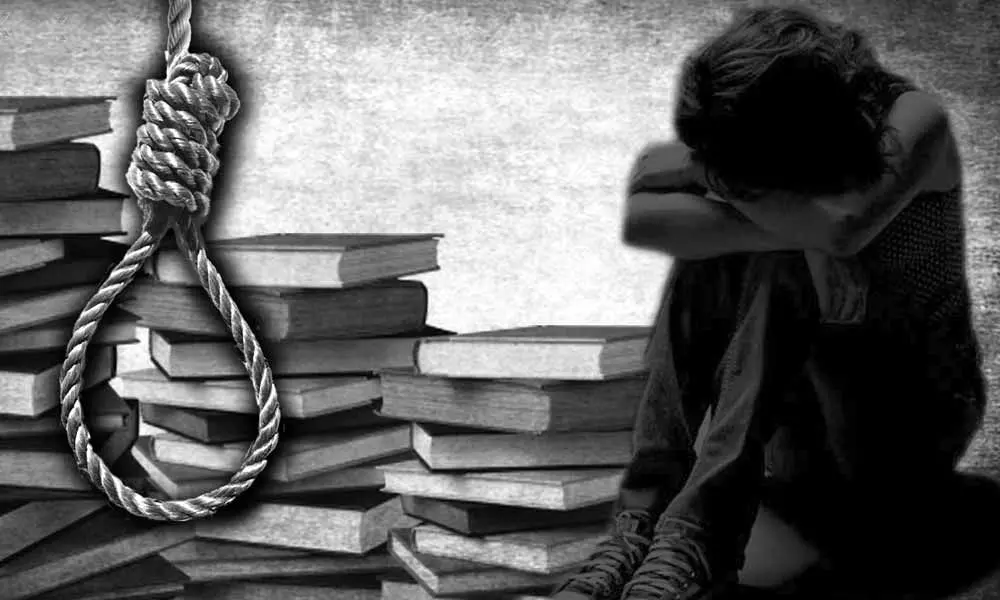

Her father is a security guard in a bank. The whole family wanted Niharika, the eldest daughter to shatter some glass ceilings of aspirations and qualify for a good engineering college via the Joint Entrance Exam (JEE). Instead, it is the family of Niharika that lies shattered. On January 29, Niharika Solanki, who lived in notorious Kota, hanged herself inside her room at their home ad left behind a hauntingly distressing suicide note that said: “Mummy, Papa, I can’t do JEE so I commit suicide. I am a loser. Worst daughter. Sorry Mummy Papa. Yehi last option hai”.

According to information coming out from the tragedy, Niharika had scored 70% in her plus two board exams conducted by the Rajasthan government. The thing is: the National Testing Agency requires that you end to score at least 75% in your school board exams to be eligible to sit for the JEE which is the gate away to premium educational institutions. It seems Niharika was studying and attending coaching classes to sit again for the board exam to take her score above 75%. Unlike almost all other student suicides that occur in Kota in hostels, this was a tragedy brewing at home. In the near future, Niharika will be a statistic, one of the three dozen odd youngsters who have committed suicide in the notorious coaching factories of Kota.

The bigger tragedy is: she might not have died. All that was required for her family to tell her to be happy with her 70% and that there are numerous other career and livelihood options for her to follow. In traditional Indian families, one adage often told to children is that while all five fingers are important, they are not the same. Sadly, when it comes to real life, such lessons are rarely followed. Niharika’s family is a classic example of aspirational Indian families. They are the first generation to break out of poverty.

They give immense value to education and know instinctively that education will propel their children towards middle class status. But a peculiar combination of ambition, ignorance, peer pressure and wrong choices leads to tragedy. Not all such cases end up in suicide. But there are hundreds of thousands of broken dreams and unhappy souls who chased what they should not have in the first place.

In 2023, when the author started this column, one of the first topics picked up to discuss and analyse was the dazzling array of “unconventional” careers that youngsters of contemporary India could choose from. There was this real-life example of an ambitious “corporate” type who discovered the magic of cloud kitchens during the Covid lockdown and realised she could harness her passion for food and cooking to become a successful entrepreneur. She has become.

There is this domestic help who trained as a beautician, joined a service aggregator and now earns five times what she did as a domestic help. There is the other one who is a successful travel blogger cum vlogger with a huge number of subscribers on YouTube. Just recently, social media was awash with pictures of a gentleman delivering gas cylinders. He happens to be the father of Rinku Singh who now plays cricket for India and has become famous for his sensational shots.

When such a wide plethora of livelihood options are available, why do millions of young Indians bang their heads against the proverbial wall seeking “safe” and “secure” jobs? As mentioned earlier, it is ignorance, peer pressure and the failure to realise your true skill sets because you are immersed in giving entrance and competitive examinations. Because of his background, Niharika’s father would not have been aware that his daughter could still lead a successful and meaningful life without being obsessed with an engineering degree.

The key lies there. How do stakeholders bridge this information gap, particularly for aspirational Indians? There is no doubt that if parents and their children have access to credible and reliable information on the wonderful opportunities that a whole range of other career options provide, they would not confine themselves to equating success with engineering, medicine or that ultimate prize: a government job. How does one ensure such information reaches aspirational families on a regular basis?

This is the age of smart phones, virtual classes and digital learning. The author is convinced there should be a minor tweak to the new educational policy where it would be compulsory for schools to take the help of professionals and inform students about, let’s say 60 career options. When students in senior school show genuine interest in one such career option, they should be encouraged to learn more and more about them through digital tools.

Young students are anyway immersed in their smart phones through the day. Why not encourage them to leverage the smart phone to chase dreams they can relate with; not what tradition dictates. India has a population of 1450 million. There will never be enough “jobs” for all young Indians. The smarter thing is to look for “alternative” avenues.

(Author has been a media professional for over 3 decades. He is now Executive Director, C Voter Foundation. Views are Personal)

Great insights! Thanks for sharing.