Prof Mrinal Chatterjee

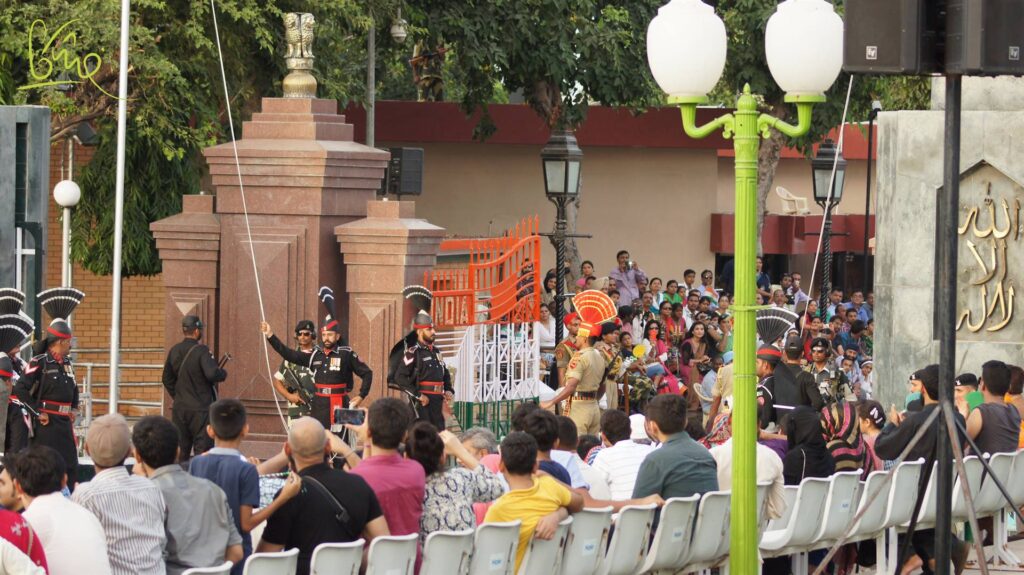

The Partition of India was violent and traumatic. It was poorly planned and executed in haste. Never before in the history of mankind had such largescale violence and displacement of population taken place, not even in holocaust.

At a conservative estimate more than one and a half million people died in the violence following the Partition. Countless women and children suffered atrocities of the worst kind.

Though India and Pakistan share a common culture, and people of both the dominant religions – Hindus and Muslims – have been living together for ages, (some historians believe from the later part of the seventh century), the incidents of violence escalated to an unprecedented scale and level in the four year before 1947. The resultant trauma was deep. Feelings of acute insecurity, vacuum, gloom, and depression gradually pervaded both communities.

Every largescale tragedy often gives birth to great art and literature. It happened with partition of India too. From the 1940s itself, films, literature and other art forms have engaged with the consequences of partition, even as a large section of people and politicians were hell bent on dividing the country on religious lines.

After the partition, which saw violence and brutality at an unprecedented scale, poets, litterateurs, painters and filmmakers depicted the violence and the bleeding faces of the uprooted people who, faced with formidable socio-economic and political odds, dreamt of finding a new home, though carrying in their hearts the memories of a lost homeland. They also portrayed the selfishness and degradation of human relationships. Hope and hopelessness found equal space in their oeuvre.

Films by Nimai Ghosh, Ritwik Ghatak, MS Sathyu, Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Chandrapakash Dwivedi, Pamela Rocks, Deepa Mehta, Kamal Hassan, Gurinder Chadha, Nandita Das are many others are seen as authentic and complex documents of the tragedy.

Writers and poets like, Nanak Singh, Amrita Pritam, Khushwant Singh, Bhisham Sahni, Rajendra Singh Bedi, Saadat Hasan Manto, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Atin Bandopadhyay, Tapan Roy Chowdhary, Prafulla Roy, Narendra Mitra and scores of others depicted that in words.

Painters like Jatindra Chowdhury, Satis Gujral, Paritosh Sen did that in their paintings.

Indian films, literature, performing and plastic arts have depicted that “the Partition of India was not merely a division of a geographical landmass, but that’s significance lay deeper, in the suffering of the separation between people, in the sufferings of losing one’s dear and near ones, and in the sufferings of being uprooted from the homestead of one’s ancestors.”

While photographs recorded the history with all its brutality and sorrow, disappointments and hopes and aspirations- cartoons mocked the mighty, showed what led to the situation and what was happening.

To the credit of all the artists, directors and litterateurs- none pointed finger at the other community. Indian partition literature and visual arts are significant for the absence of such blame-game. The loss was at both the sides. The sadness was all pervading. All art forms lamented for what happened and searched for ways to reconcile and pre-empt its repeat in future. There lies the silver lining; there lies the hope for humanity.

In many of the recent writings on partition including Geetanjali Shree’s 2022 Booker winning novel ‘Tome of Sand’ focus on nostalgia and reconciliation. Many young writers, artists, film makers and digital content creators on both sides of the border are focusing on reconciliation and peace.

However, there is a political interest on both sides of the border to keep the fire of hate and mistrust burning. In Pakistan the army’s existence and inflated budget and influence rest on this.

Can peace win?

Hope it does.

(The author is Regional Director Indian Institute of Mass Communication, IIMC Dhenkanal. Views are personal)