Sutanu Guru

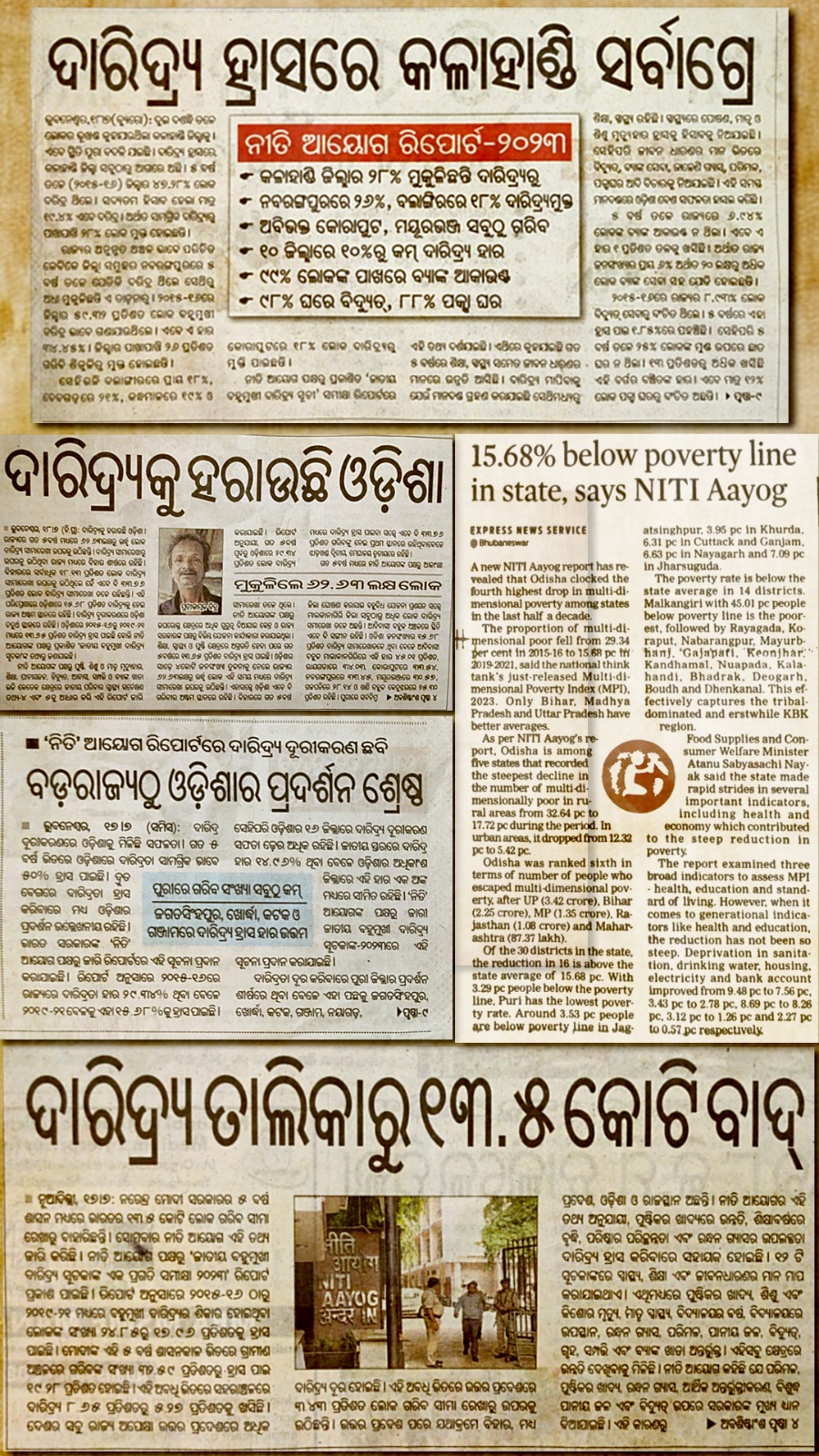

“I would urge analysts and commentators in Odisha to patiently go through the 400 plus page Niti Ayog report and check the data and numbers for themselves. Out of 30 districts in the state, 16 have poverty ratios that are superior to all India average. The least poor district is Puri with a poverty ratio of 3.29%, comparable to districts in states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu.”

My jaws dropped as I went through the numbers. For someone born in Sambalpur, Odisha who had seen abject and dehumanising poverty in the state in the 1970s and 1980s, these numbers appeared too good to be true.

But the numbers are credible because they have been based on data collected by the fifth round of National Family Health Survey. And they have been released by Niti Aayog and endorsed by UNDP and Oxford University. Not that endorsement from Oxford matters, but the data simply floored me.

I am talking about the latest progress report released by Niti Aayog on multi-dimension poverty in India on July 17, 2023. Sambalpur district, where I was born has just one in ten citizens who are categorised as multi-dimensionally poor. The national average is 14.96%. The overall poverty ratio for Odisha according to this report is 15.7%.

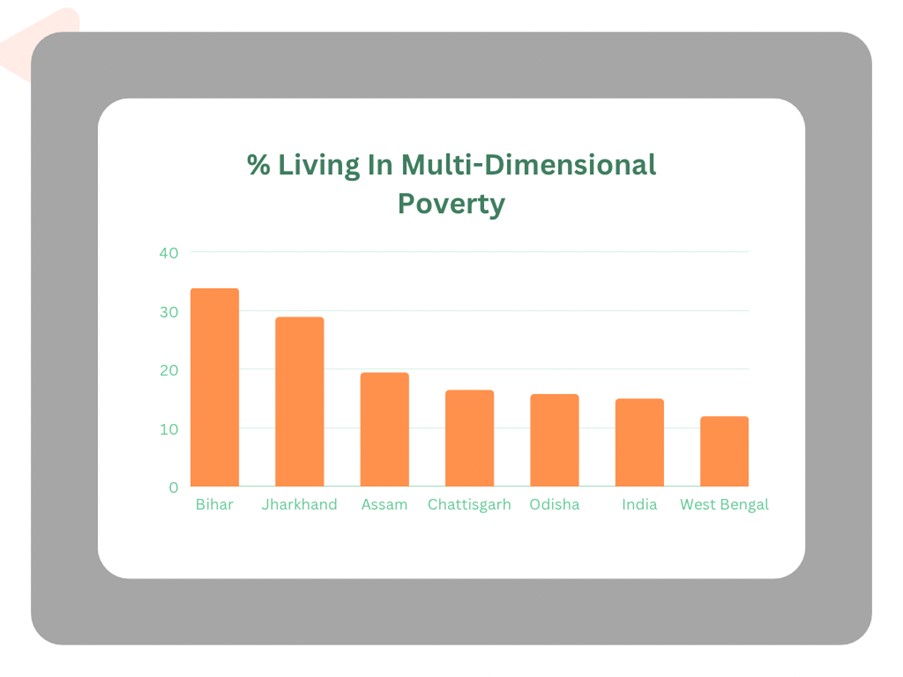

Once upon a time, Kalahandi district was considered to be the epicentre of poverty and starvation. This district had a multi-dimensional ratio of almost 50% in 2015. By 2021, it had dropped to a shade below 20%. Barring West Bengal, Odisha outperforms all the “eastern” states that have been chronically poor since independence in 1947.

West Bengal was 8 percentage points ahead of Odisha in 2015. Now it is about 4 percentage points ahead. Don’t also forget the fact that when Odisha was a cesspool of poverty in the past, Bengal was one of the most industrialised states in India. In some previous columns, I have argued how the chief minister of Odisha Naveen Patnaik has consistently outperformed his much-hyped Bihar counterpart Nitish Kumar.

Naveen Babu has not only done far better than the so called Susashan Babu Nitish when it comes to winning elections but has delivered genuine and seemingly miraculous change in his state. I have seen criticism of his government; particularly his penchant for relying on bureaucrats over his political colleagues on issues related to governance. Many have remarked that he has defanged the media in Odisha with a carrot & stick policy.

Some even say that the achievements of his regime are a mirage. Having lived outside Odisha since 1983-except a brief 100-day stint and frequent visits, I do not have the expertise to comment on that. But I not only trust, but also worship credible data. And data in the latest Niti Aayog report on multi-dimensional poverty clearly indicates that Naveen Patnaik has not delivered a mirage but a near miracle.

What is multi-dimensional poverty? Traditionally poverty was measured by taking into account family income, expenditure and consumption. But more than three decades ago, the UNDP came up with a term called “human development” and released a global Human Development Index.

The logic is: well-being and quality of life of a family depend on many factors related to health, education and access to basic necessities apart from just per capita income or expenditure. Human development is now universally accepted as a better measure of poverty and quality of life.

The Niti Aayog takes into account 12 parameters related to health, education and standard of living to measure multi-dimensional poverty. There is no doubt whatsoever that it is the most credible estimate of poverty and quality of life available today for India. The first Niti Ayog report was released in November 2021 and the author wrote extensively about it back then. This updated progress report has been released on July 17, 2023.

And it reaffirms what was visible in the 2021 report: that Odisha has done astonishingly well in reducing poverty. Just imagine: the multi-dimensional poverty ratio of Gujarat is 11.66% while that of Odisha is 15.68%. I know there still are pockets of extreme poverty in Odisha. The bigger problem is livelihood opportunities for unskilled and skilled youth within the state.

That is why Odia youth are found in huge numbers as migrant workers in states like Gujarat. Yet, what Odisha has achieved in this century calls for non-partisan applause.

I started this column by mentioning how my birthplace Sambalpur district has a multi-dimensional poverty ratio that is superior to all India average. I would urge analysts and commentators in Odisha to patiently go through the 400 plus page Niti Ayog report and check the data and numbers for themselves. Out of 30 districts in the state, 16 have poverty ratios that are superior to all India average. The least poor district is Puri with a poverty ratio of 3.29%, comparable to districts in states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

A separate column co-authored by me for a national media platform points out that just six or seven traditionally poor states account for more than 70% of the poor population in the country. Take them out of the equation and India is actually a middle-income country with a reasonably decent standard of living. Within Odisha, the same argument holds for six or seven districts. One can look at their performance and status in two ways.

One is, like mentioned earlier in the case of Kalahandi, admire the manner in which poverty has plummeted from about 50% to less than 20% in just six years. The other way of looking at the data is to say the persistence of chronic poverty in six or seven districts’ signals governance failure. In my opinion, both arguments would be valid.

A deeper dive into the data reveals that eight districts, namely Malkangiri (45%), Raygada (34%), Koraput (33.5%), Nabrangpur (33.4%), Mayurbhanj (30.5%), Gajapati (28.1%), Keonjhar (26.8%) and Kandhamal 25.3%) account for most of the poverty prevalent in Odisha.

It is not a surprise that many of these districts are also hotbeds of Maoist terrorism and a civilisational war between the RSS led Sangh Parivar and Christian missionary outfits. On almost all parameters, these districts show why Odisha and India still remain Third World despite tremendous strides made in the last three decades or so in terms of economic growth.

I am no policy expert and have no concrete suggestions on how to lift these districts to Second World status like their dozen odd counterparts within Odisha. But if poverty of this scale and magnitude persists even in the future, it will be a blot on the otherwise marvellous legacy of Naveen Patnaik when he hangs up his boots. I would still prefer to dwell on positives and hope that the near miracle achieved in other parts of Odisha is repeated in the chronically poor districts.

Now let us do some concluding number crunching. Why has Odisha performed so well in reducing multi-dimensional poverty? And, if it has done so well, why does it still lag behind all India average though the gap is very small? A closer look at data has answers to both questions.

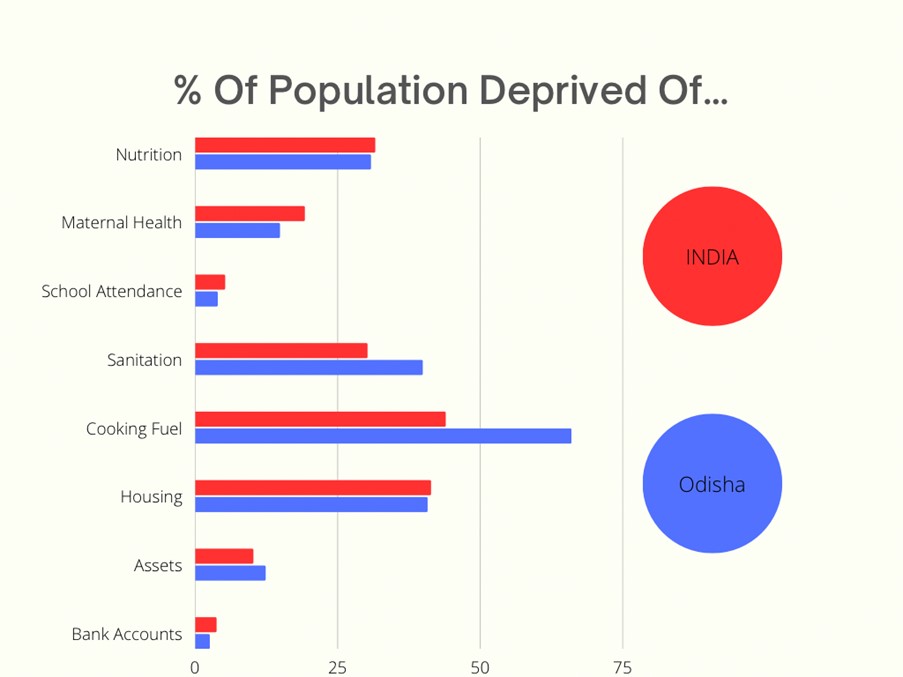

As the chart shows, Odisha performs better than India on most parameters. When it comes to access to adequate nutrition, maternal health, housing, school attendance, electricity and bank accounts, Odisha performs better than India as a whole. That explains why Odisha has emerged as the star performer among traditionally poor “eastern” states.

But it is a big laggard when it comes to sanitation and cooking fuel. While a shade more than 40% of India is still deprived of access to clean cooking fuel, two thirds of the residents of Odisha are deprived of it. Similarly, while 30% of India is categorised as without access to modern sanitation, the figure for Odisha is close to 40%. These numbers explain why Odisha still lags behind India, albeit marginally.

Frankly, I am baffled with these numbers. If more folks in Odisha on an average have pucca houses and bank accounts and have almost the same ownership of assets as India, what has prevented them from getting gas connections? I am not talking of buying increasingly expensive LPG gas cylinders every month or so; but having a gas connection. Has the Ujjwala scheme been such a spectacular failure in Odisha?

That debate is for another day. As of now, it is time to acknowledge that Odisha has done remarkably well in reducing poverty in this century. If you disagree with that then you clearly don’t respect data and facts.

(Author has been a media professional for over 3 decades. He is now Executive Director, C Voter Foundation. Views are Personal)