Bhaskar Parichha

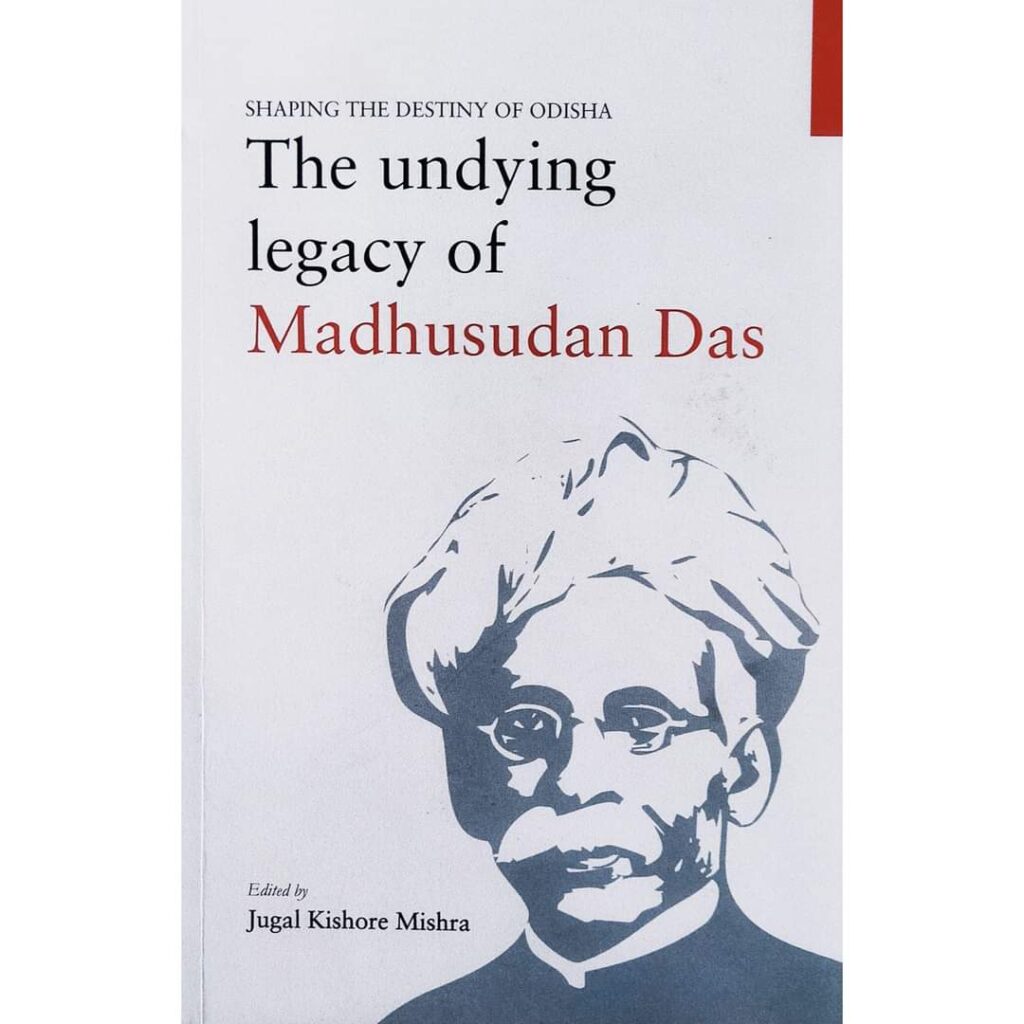

Title: The undying legacy of Madhusudan Das

Author: Jugal Kishore Mishra

Publisher: Madhusudan Das Research Chair / KISS

Bhubaneswar

Known as ‘the grand old man’ of Odisha, Madhusudan Das was a pioneer of Odisha’s unification and women’s rights. The lawyer who unified Odisha and reformed the Indian judiciary. He stood up for his people. Madhusudan led the linguistic movement that united Odisha. His contribution to the social and economic upliftment of Odisha’s people is truly remarkable. Mahatma Gandhi and B.R. Ambedkar held Madhubabu in high esteem. Gandhiji called him a “great philanthropist” and Ambedkar praised him for his speeches on caste and Dalit issues.

The Madusudan Das Research Chair of Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS) has attempted to combine diverse perspectives on Madhubabu in a book. It is an outstanding tribute to this venerable soul of Odisha.

Edited by Prof. Jugal Kishore Mishra, ‘The Undying Legacy of Madhusudan Das’ has a galaxy of contributors who have delved deep into Madhubabu’s legacy. Their opinions are conspicuous, erudite and pragmatic.

Jugal Mishra has taught political science for more than four decades. He has several publications to his credit. Prominent among them are ‘State Politics in India’; ‘Indian Political Thinkers’; and ‘An Anthology of Dalit Studies’. Prof Mishra attended several conferences and seminars in India and abroad. He was also president of the Indian Political Science Association.

According to the blurb: ‘The two dozen plus papers seek to illuminate aspects of the rich legacy of Madhusudan Das. He played a key role in shaping modern Odisha’s destiny through his vision and valuable initiatives. His vision has lost no relevance in our time. It continues to provide inspiration and guidance to those who strive to build a better future for the state and the nation.’

Noted academics analyze, celebrate, and acknowledge Madhusudan Das’ seminal role. Considering the significant role Madhubabu played in laying the foundation for Odisha’s resurgence, these articles attempt to capture these influences in a comprehensive manner.

In the introduction, Jugal Kishore Mishra writes: ‘Madhusudan Das was deeply disturbed when he learned Hamilton’s (Sir George Hamilton – the Secretary of State for India) disparaging comments on Lord Jagannath. To Hamilton, the idol worshipped as the Rashtra Devata of Odisha in the Jagannath Temple,Puri was just a piece of unshaped woodwork, just a piece of blood-red log of wood. So Madhusudan lambasted Hamilton. He said, ‘Does Hamilton have eyeballs in his eyes? If yes, are they made of stone? How could the Puri Jagannath Temple of my Orissa appear ugly to him?

In reality, the British are traders and salesmen. Yet there are some good aesthetics among them and they value the beauty of Oriya art and sculpture. It remains unsaid that Madhusudan Das himself was a dedicated promoter of Odia art and sculpture. He cared about Odia art. In England he held many exhibitions showcasing beautiful specimens of Odisha art and sculpture. To those who promoted Odisha, he gave samples of Odia art and sculpture.

According to the outline of this 250-page anthology, Madhusudan Das was not a jingoist. Madhubabu said those who reside in Orissa (whether born here or outside of Orissa) and own their own home or rent a home are considered Oriyas. All such Oriyas are brothers to one another; all have a mother in Orissa for their sustenance.

For Madhusudan, the book argues, no Odia, while loving Odisha, turns against or forgets her mother India. Therefore, he could not imagine India without Odisha, nor conceive of Odisha without India. Madhubabu’s most sacred mission was to glorify Odisha to enhance her national identity.

Prof. Mishra observes: ‘Madhusudan Das was a staunch believer in the power of education in general and women’s education in particular to transform society. That was why, during his tenure as minister, he took steps to promote education in Odisha. Only because of the support of Mr. Das, on 8th February, 1908, a Girls’ School with only 15 students was established. By 1909, the school had 300 students on its rolls. Shoilabala also helped him immensely in this endeavor. She could secure the support of Sir E Baker, the then Lt. Governors of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. They. They set up the school so that girls in Orissa could receive an education. Madhusudan had himself inspired Shoilabala and Sudhanshubala to pursue higher studies. Sudhanshubala had not disappointed Babu. She was the first woman advocate in Odisha.’

A staunch feminist, Das fought an inherently patriarchal system to open the legal field to Indian women. While most credit Cornelia Sorabji as India’s first female lawyer, historians say that it was Das’ adopted daughter, Sudhanshubala (Hazra), who broke all shackles to emerge as the country’s first female lawyer in 1923. Madhubabu fought Hazra’s case in the Patna High Court in 1921, winning and instating her as a lawyer in 1923. This was almost a year before Sorabji.

Madhubabu’s cultural role was amazing. Mishra says Madhusudan, the culturalist, worked untiringly and unselfishly to promote Odia culture. Only through his efforts, Ravenshaw College emerged as a beacon of academic excellence on India’s east coast. To encourage Odia culturalists to dedicate themselves to making Odisha culturally rich, he constructed suitable monuments. The books deal with several other aspects of Madhubabu’s magnificent life of equal significance.

With a foreword by Dr Achyuta Samanta, Founder KIIT & KISS and a preface by Prof Deepak Kumar Behera, Vice-Chancellor, the volume – comprising writings on the dedicated life and works of this revered leader, statesman and thinker – will be of immense value for younger generations.

The book is sure to enhance the acquaintance of those who hold high regard for one of Odisha’s most illustrious sons.