Dr. Bhagaban Jayasingh

Like art and literature, as well as music and dance, the film has become one of the extraordinarily popular forms of expression or communication. At present films are no longer viewed as “just entertainment” but as a representation of our culture, religious beliefs, myths and archetypes, our language, and overall attitude to life and the world. One must understand that film is a significant agent in the transmission of culture.

In Odisha, filmmakers have tried, though not very successfully, to use film as a cultural medium for the articulation of the “identity” of its people in terms of their culture, art, literature, dance forms and architecture, etc.

Historically, the cinema, according to Malanie J. Wright, refers to “not just films,” but “institutions” that “produce and distribute them, and the audiences who are their consumers.” History of cinema spans a little over a century since the Lumiere brothers invented the technique, and released their film “The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station” on January 25, 1896. Though cinema attendance has declined over the years in the West, it has shot into a worldwide phenomenon of a roaring business in the mid-twentieth century.

In India, film still continues to be the enormously popular medium of social pastime. We have traveled many miles and crossed many milestones of success ever since “Raja Harischandra,” India’s first silent film, directed and produced by Dadasaheb Phalke, appeared on screen in 1913. Now India has become the largest producer of feature films in the world.

According to statistics, around 11 million people visit over 13000 cinemas across India everyday, and this is besides the NRIs watching hundreds of films everyday. India produces around 800 films every year as against 450 that are produced in Hollywoods, though the onslaught of the Covid-19 has impacted the production to a considerable extent.

Over the years, hundreds of novels, plays, songs and short stories have been written on what is claimed to be the “Jagannatha Culture,” “Jagannatha Cult,” or the “Jagannatha Chetana ” or consciousness. All our regional art, culture and literature revolve around Lord Jagannath and countless myths and legends surrounding the Lord’s existence. In the early major-release films, filmmakers tried their best to bring critical Jagannath consciousness to bear on their films. It is because Lord Jagannath is perennially linked with the patterns of our life, or shared experience, or our common behavior as Odias. It is one of the ways that the people of a community pattern their lives and attitude to life; and its inherent traits are passed from generation to generation.

Religion plays an important role in the production and success of film as a rich blend of tradition, myths, history and language. Like any other major religion of the world such as Buddhism, Islam and Christianity, Hinduism also transmits its message through sound and image.

The increasing use of various electronic and digital media — radio, video, television, CDs and the internet — helps people realize the importance of “the network society,” which has been trying to forge a new relationship between media and religion.

The religious landscape of Odisha has always been embellished with an astute faith in all-out benevolence of all-merciful Lord Jagannath. The filmmakers tried to show how films could use religious imagery, characters, and symbolism primarily from our rich Jagannath culture to reach out to the greater mass of filmgoers. The characters like Dasia Bauri, Bandhu Mohanty, Shria Chandaluni have caught the imagination of people as great devotees who had glorified an unflinching faith in the Lord. There is the story of Salabeg, a Muslim devotee, who was cured of a deadly disease with His blessings, had written hundreds of bhajans in praise of God.

Lord Jagannath has been worshiped even before their wooden images got installed in the sanctum sanctorum. In the earliest periods of history the non-Aryans, the autochthonous sevakas, worshiped Him in the distant mountainous regions of Odisha. Then Aryan king Galamadhab, through the help of Vidyapati, managed to snatch away the blue stone image of the Lord from the possession of tribal chieftain, and consecrated it on a mound at Puri. Subsequently, the deities manifested themselves in the wooden images that symbolized a synthesis of all dharmas, preaching tenets of peace, harmony and fraternity or universal brotherhood.

Most of the early filmmakers concentrated on the popular legends and myths about Lord’s descent on earth, though the fact is still shrouded in mystery. It is believed that after the death of Lord Krishna, some of His mortal remains– called Brahma– lay floating in the sea on Odisha’s seacoast. The Sabar chief, Viswabasu collected the floating Brahma from the sea and worshiped him as Nila Madhaba. “Nila” refers to the sapphire blue color of Brahma whom he worshiped as an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. A great worshiper of Vishnu, Indradyumna, the King of Malwa, made a frantic attempt to retrieve Nila Madhab from the possession of the tribal chief.

He sent a Brahmin emissary named Vidyapati to locate His shrine in the forest. Vidyapati had to marry the tribal chief’s daughter Lalita to succeed in his mission. On receiving the information regarding

the exact location where the blue stone lay hidden the King of Malwa made an expedition to the jungle. But to his great shock and disbelief, the stone image had already disappeared.

The distraught king made a frantic prayer to his Lord who appeared in his dream and instructed his devotee to collect a floating log from the sea. The log he collected carried four different marks of Lord Vishnu: “shankha” (conch), “chakra” (wheel), “gada” (mace), “padma” (lotus). The Lord then instructed the king to carve out the images for their installation on a pedestal in the sanctum sanctorum.

Several films built on this primary myth or legend included “Lalita,” (1949) “Shri Jagannath,” (1950), and “Shri Shri Patitapaban” (1963). Some 29 years after “Shri Jagannath” was released, a film bearing the same name appeared on screen in 1979. The screenplay was written by Bijay Mishra, a very well-known playwright of the sixties and directed by K. Vijay Bhaskar, an illustrious name in Telugu film industry. Some well-known actors of the Ollywood appeared in the film: Jharana Das (Queen Gundicha), Chakrapani (Vidyapati), Meenushree (Lalita), Kedar Guru (King Indradyumna) and Dhiren Das (King Galamadhab).

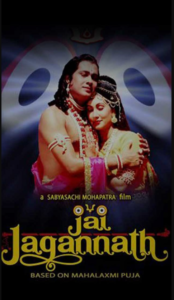

The film “Shri Shri Patitapaban” produced in the year 1963, was directed by Sukumar Ganguli with artistes like Laxmipriya Mahapatra, Radhamani Mahapatra and Nityanand Misra. In all these films, which were based on the life-story of the Lord, Jagannath played a key role whether as an image of religious inspiration, or at the background, causing things to happen as per the divine will. In 2007, Sabyasachi Mahapatra produced a film, “Jay Jagannath,” simultaneously in 14 Indian languages, besides English. Based on Balaram Das’s “Laxmi Puran,” the story of this multi-lingual, socio-mythological feature film, swept up a clutch of awards at regional and national levels, and received glowing accolades from film critics.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize the importance of film studies for furthering information about our society, culture, history, language and religious consciousness through intensive research into film which remains largely unexplored. One has to concentrate on film study as a full-fledged academic discipline and show to the world the richness of our religion and culture as an inextricable part of Jagannath consciousness as reflected in our films.

(Dr. Bhagaban Jayasingh is an eminent bilingual writer. He is also an Academician by profession with long experience, currently working as Dean, School of Communication ASBM University, Bhubaneswar. Views are personal).