Dr. Mrinal Chatterjee

On 8 August 1942 at the All-India Congress Committee session held at Gowalia Maidan in Bombay, Mahatma Gandhi launched the ‘Quit India’ movement. He gave a call for ‘Karo ya Maro’ – Do or Die.

The British Government swung into action almost immediately and arrested almost all front-line Congress leadership including Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel under the ‘Defence of India’ Rules. The Working Committee, the All India Congress Committee and the four Provincial Congress Committees were declared unlawful associations under the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1908. The assembly of public meetings was prohibited across the country.

However, the movement erupted across the country like volcano, even without the top leaders and under severe repressive measures. Aruna Asaf Ali, then just 33 years old, unfurled the national flag at Gowalia Maidan in Bombay. In several places, across the country local leaders declared freedom and formed ‘National Government’s- though most of them could survive only for few weeks. Without the top leaders and a well laid out strategy, the movement became rudderless. As a result most demonstrations had been suppressed by 1944, though upon his release in 1944 Gandhi continued his resistance and went on a 21-day fast before he called off the movement.

Though the Quit India movement failed to immediately dispel the British from India, it showed the mood of the public which eventually led them to quit India. There were other socio-political and geo-strategic reasons too. By the end of the Second World War, Britain’s place in the world had changed dramatically and the demand for independence of India could no longer be ignored.

The lesser-known part of Quit India Movement

Many of us know about the role Gandhi and other senior leaders played in this movement. However, not many know about the leaders at the grass root level. In fact, a significant feature of the Quit India Movement was the emergence of what came to be known as parallel Government in some parts of the country.

The first one was proclaimed in Balia in East UP under the leadership of Chittu Pandey. Pandey, popularly known as Sher-E-Balia (tiger of Balia) was born in Rattuchok, a village in Balia district in UP. He led the Quit India Movement in Balia. He headed the ‘National Government’ declared and established on 19 August 1942 for a few days before it was suppressed by the British. However, the ‘National Government of Balia’ succeeded in getting the collector to hand over power and release all the arrested leaders. In Bihar under the leadership of Jugal Choudhury peasants fought with the British troups with lighted torches and boiling oil and for some time took over the justice dispensation system.

In Satara, Maharashtra people set up a parallel Government known as ‘Prati (which means parallel in Marathi) Sarkar’. Nana Patel was the head of the Government that lasted for some months. Y. B. Chavan and Achyuta Patbardhwan were the other prominent leaders of the movement. Satara emerged as one of the bases on resistance. It was a guerrilla type of struggle, operated in over 150 villages with overwhelming peasant support. There were raids on taluka treasuries and armouries. The Prati Sarkar took over many of the functions of the government. This Parallel government established many public utilities like a market system, supply and distribution of food-grains and a judicial system to settle disputes and penalise dacoits and robbers, pawnbrokers and money lenders. Law and order was entirely in its hands. Under this government an army was formed named Toofan Sena. It fought the imperial government by attacking its major establishments like the railways and postal department. However, the ‘prati sarkar’ fell by 1946 because of several internal and external reasons.

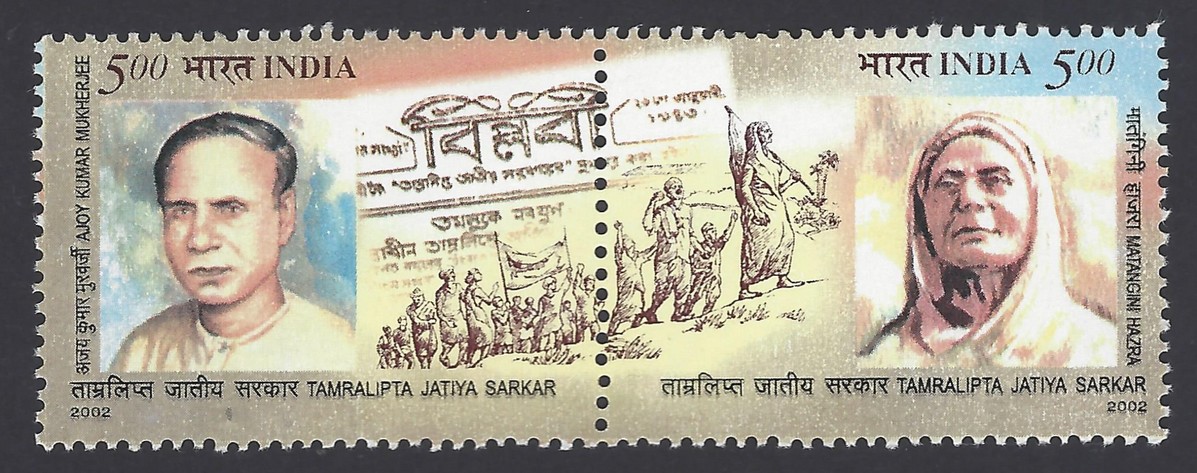

In Tamluk, West Bengal the ‘Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar’ (Tamralipta National Government) functioned for almost two years from December 17, 1942 to August 8, 1944. The chief protagonists were Satish Chandra Samanta, Sushil Kumar Dhara, Ajoy Mukherjee and Matangini Hazra. It had its own newspaper Biplabi.

Though it was initiated by the call of Gandhi, but it did not confine itself to the realm of the principles of Gandhian practice. So far as the region of southeastern Midnapore was concerned the contradiction between the non-violent and violent forms evaporated in the face of severe repression perpetrated by the British military-bureaucratic regime. It was not Gandhi’s ‘ahimsa’ which moved the rebels of Midnapore so much as his precept ‘Do or Die’. A good deal of underground literature (including that of the ‘Biplabi’, the mouthpiece of the Tamralipta jatiya Sarkar) cropped up with that precept as the motto.

It happened in Satara in Maharastra and also in Bihar and other places. Non-violence took a back seat and people resorted to violence- even organized violence. In several places- unchecked violence became the cause of it losing public support.

In his analysis of the specific nature of the movement of 1942 in Midnapore, Dr. Partha Chatterjee notes that many senior Congress leaders of the area “both in and out of prison at the time of the movement, did not approve of the methods adopted. But the new leadership had no compunctions about ‘violence’. In the initial stages of the movement, each action involved thousands of ordinary peasants engaged in collective violence against targets that symbolized the power of an oppressive colonial state. The leadership coordinated the location and timing of these acts. The supposedly spontaneous violence of peasant resistance was thus sought to be raised to an entirely different level, where violence becomes a strategic element in a much more extended, differentiated and complex process of institutionalized politics.

But somehow it did not succeed, and the movement ended not with a bang but with a whimper through it was not a complete failure. While addressing a vast gathering assembled at an evening prayer meeting at Mahishadal in Tamluk on December 28, 1945 Gandhi said: “Whatever sufferings you had for the sake of swaraj have not been in vain. It will bear fruit-one day. No big thing could be achieved without suffering or sacrifice”. He further added that people should always remember that immense sufferings and sacrifice were needed for realization of God and that they could not attend swaraj without sufferings.”

India had to wait for two more years to get independence. But, that is another story.

(Journalist turned media academician Mrinal Chatterjee works as a Professor and Regional Director at Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC), located at Dhenkanal, Odisha)