Sutanu Guru

Odisha’s share of bank credit backed investment project proposals increased from 2.2% in 2021-22 to 11.8% in 2022-23 as per RBI

Political analysis and discourse in Odisha is now focused on two things: the first is how the national leadership of the BJP has “thrown the state unit to the wolves” by wooing Naveen Patnaik.

The second is the extraordinary tale of bureaucrat V. K. Pandian increasingly donning political colours. I am intrigued but not really that interested. Elections will anyway tell us about the implications of the two. What interests me more is the so-called economic miracle in Odisha. Recently, The Indian Express published a detailed front story that had some astonishing data.

The story quoted a study by the Reserve Bank of India to say that Odisha’s share of bank credit backed investment project proposals increased from 2.2% in 2021-22 to 11.8% in 2022-23. It ranks third in value of total committed investments after Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat. Look at it another way: Odisha got committed investments for new projects of Rs 35,000 crores. In contrast, West Bengal got Rs 3,500 crores.

In a previous column in this platform, I had argued with data how Odisha has become richer than West Bengal with a higher per capita income. This latest data set shows the “economic miracle” of Odisha is not a mirage and not mere hype touted by sycophants of Naveen Babu.

Every student of basic economics knows that such massive investments lay the foundation for faster rates of economic growth in a state or a country. It needs to be mentioned here that the figures are not proposals announced during the annual Investment Summits that almost all states organise with a lot of fanfare nowadays. These are bank credit backed concrete investment plans for new projects. The secret behind this remarkable economic transformation is sustained economic growth.

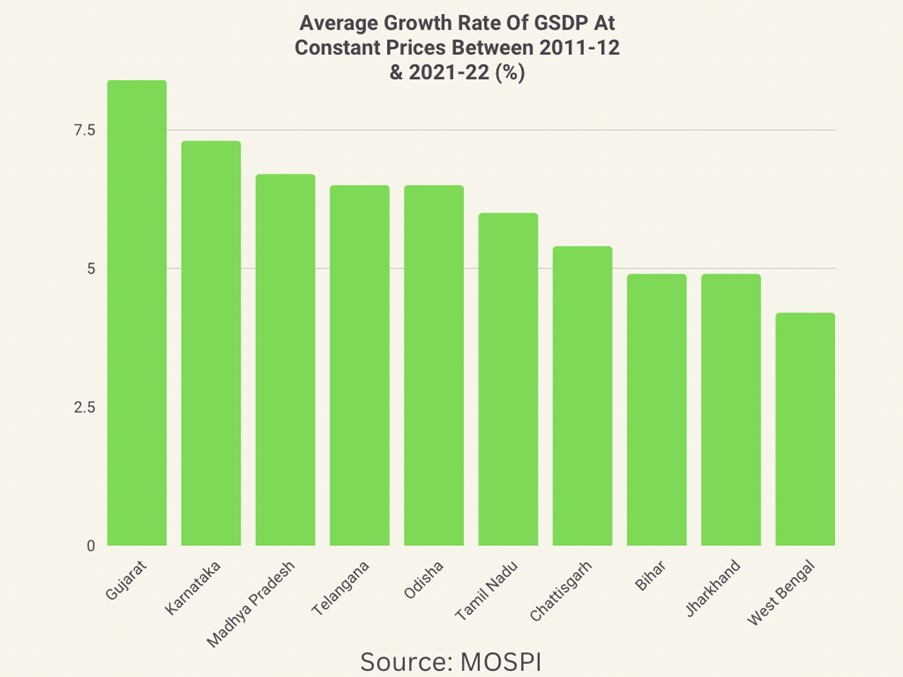

The chart above clearly indicates how the GDP of Odisha has grown at a sustained average rate of 6.5% a year for ten years between 2011-12 and 2021-22. Only four states Gujarat, Karnataka, Haryana and Madhya Pradesh have grown at a faster pace. Now, some would argue that it was easier for Odisha to register a faster rate of GDP growth because of its lower base. There is also the argument that Odisha is still miles behind states like Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Telangana, Haryana and Kerala when it comes to offering a reasonably high standard of living to citizens.

Both the argument are fundamentally correct. Look at the low base argument first. By the turn of this century, Odisha was so pathetically poor that growing fast was almost inevitable. In 2000-2001, the GDP of Odisha at current prices was about Rs 43,500 crores. That of Tamil Nadu was about Rs 1,81,000 crores.

So it should not be surprising if Odisha grew at a rapid rate this century. But there is another way to look at it. All three, Odisha, Bihar and Jharkhand were hopelessly poor with low GDP and very low per capita income by the turn of the century. Look again at the chart above. If the low base argument was always correct, Bihar and Jharkhand too should have grown at a faster pace.

But compared to 6.5% for Odisha, Bihar and Jharkhand have grown at an average of 4.9% a year over a decade. West Bengal has performed even more poorly, growing at 4.2% a year on average. The difference is significant. While Odisha is breaking out of the vicious cycle of poverty by growing fast, Bihar and Jharkhand remain chronically poor despite a low GDP base because they have failed to grow fast. At some point of time, you have to accept that governance has played a role in the comparative success of Odisha.

Let’s look at the second argument: that Odisha is still miles behind other states mentioned earlier in the column. In 2022-23, the GDP of Odisha at current prices was Rs 7,20,000 crores. That of Tamil Nadu was Rs 24, 85,000 crores. The GDP of Tamil Nadu was 3.5 times that of Odisha in 2000-21.

It is still almost 3.5 times that of Odisha. So how can one claim an economic miracle in Odisha? There is a reason. By the turn of the century, the per capita income of Tamil Nadu was about five times that of Bihar and Odisha. Now, the per capita income of Tamil Nadu is just about two times that of Odisha. It is more than five times the per capita income of Bihar. As I have often pointed out, hard and credible data always trumps over rhetoric and polemics. Once upon a time, Odisha and Bihar were the poorest two among the major states of India.

Almost everyone had written off the two as perpetual basket cases, with per capita incomes at one fourth of the all India level. Now, Bihar’s per capita income remains about one fourth of the all India average while that of Odisha is within touching distance. Chief ministers of states must be judged by what they have done for ordinary citizens in terms of improving economic well-being. By any yardstick, Naveen Patnaik is miles ahead of Nitish Kumar and Mamata Banerjee. All three have enjoyed long and uninterrupted stints in power. You judge yourself who has performed better.

But there is agony too in the story of the economic miracle in Odisha; a tale of failure. Last month, Niti Aayog released an updated report on multidimensional poverty in India that showed about 135 million Indians had exited multi-dimensional poverty between 2016 and 2021.

The performance of Odisha was spectacular. Compared to an all-India poverty ratio of 14.7%, Odisha reported a poverty ratio of 15.7%. There can be no doubt this is a remarkable achievement. But a deeper analysis of the data also reveals unacceptable failures. There are still eight districts in Odisha that report a poverty ratio in excess of 25%.

Look at the chart. Malkangiri still reports a poverty ratio of 45%. In effect, almost half the people in this district not only have very low per capita incomes, but also lack access to basic needs like health, education, toilets, clean cooking fuel, electricity and housing. To have people living in abject and degrading poverty just a few hundred kilometres away from places where the poverty ratio is below 5% means the “economic miracle” has been selective and lopsided.

To some extent, this mirrors the story of economic transformation in India as a whole. It will soon be the third largest economy in the world. But large parts of it will be still desperately poor. The legacy of Naveen Patnaik would have been stellar if Malkangiri, Raygada, Koraput, Nabrangpur and Mayurbhanj had success in reducing poverty in a substantive manner. At the moment, his legacy in terms of economic performance can best be described as good.

(Author has been a media professional for over 3 decades. He is now Executive Director, C Voter Foundation. Views are Personal)