Sutanu Guru

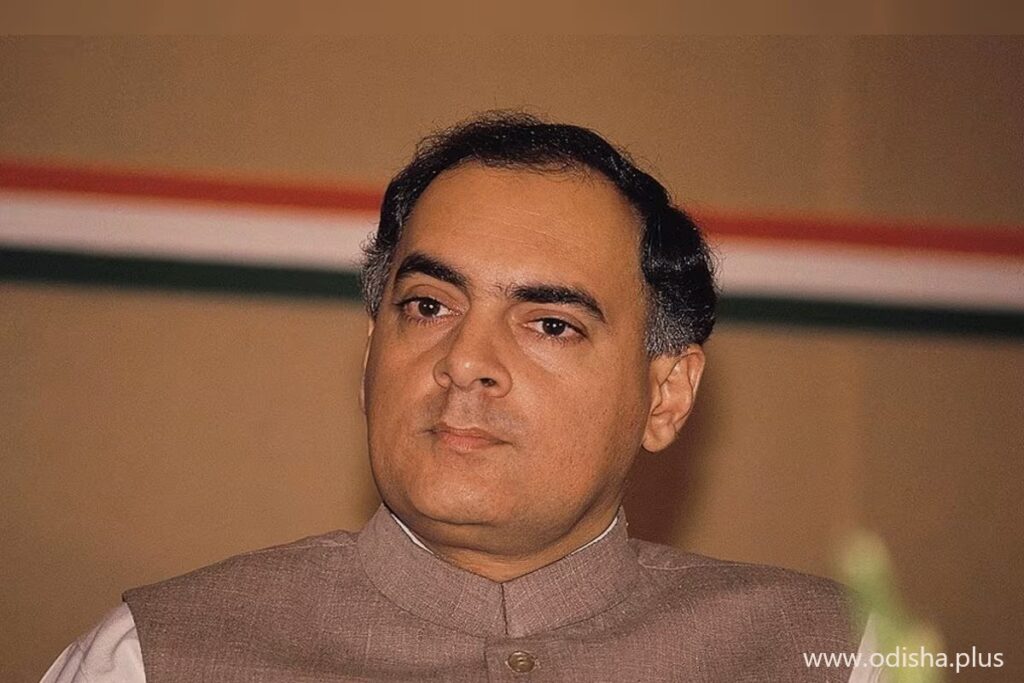

When Rajiv Gandhi became prime minister of India in 1984, the author was a student pursuing a master’s degree in economics in Pune. A few months later, when he led the Congress to the biggest ever victory in the Lok Sabha elections, the author was among the tens of millions who cheered. Like others, the author was delighted that Rajiv Gandhi was intent on building a “New India” where tired, old and outdated politicians had no place.

After all, Amitabh Bachchan had trounced the former Congress veteran H. N. Bahuguna from Allahabad and Madhavrao Scindia had inflicted a humiliating defeat on BJP president A. B. Vajpayee from Gwalior. In these times of euphoria and hope, Rajiv Gandhi was a youthful 40 years old. He spoke a new language of politics and promised real change.

He took bold initiatives and signed “peace” accords to entitle the protracted troubles in Punjab and Assam. In 1985, the Congress was celebrating 100 years. The speech delivered by Rajiv Gandhi in Mumbai to mark the centenary actually electrified the nation. His harsh words against brokers, agents and shadowy fixers who had taken control of the Congress party resonated with youngsters.

By 1989, when Rajiv Gandhi faced the Indian electorate again, the author was a full-time journalist travelling through Uttar Pradesh to cover the Lok Sabha elections. The author doesn’t know what ordinary voters in Uttar Pradesh felt and talked when they delivered the massive mandate to Rajiv Gandhi in 1984. But the mood in 1989 was euphoric in a schizophrenic way. Groups of youth would have no hesitation in screaming that Rajiv Gandhi and his coterie were thieves who were plundering India. The euphoria revolved around V. P. Singh, the Congress “rebel” who had thrown down the gauntlet. The author wasn’t very sure what the real motives of V. P. Singh were; but the youth in UP were convinced he was a saviour.

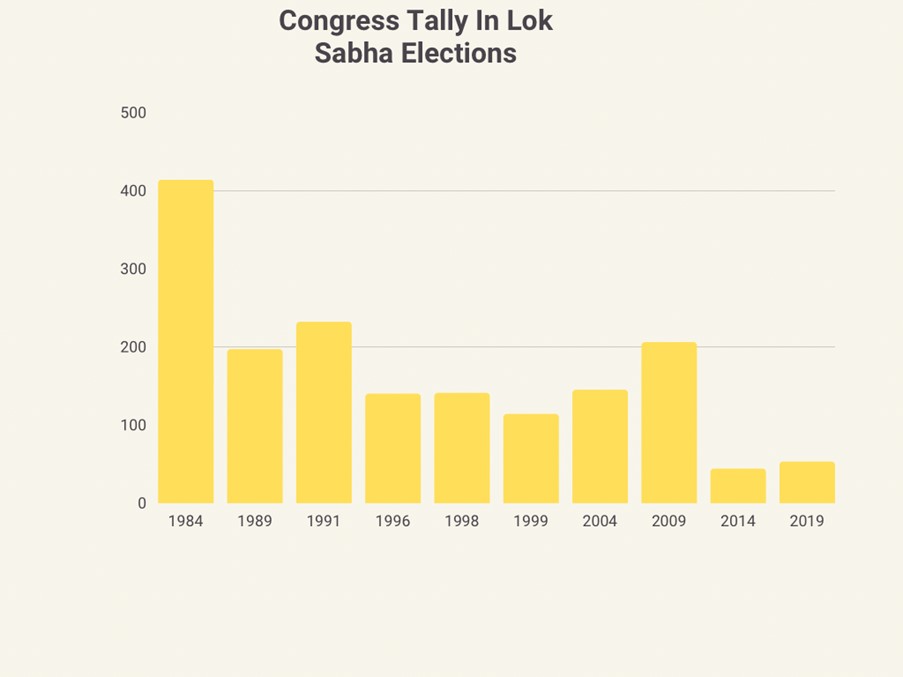

Everywhere the author traveled in a hired rickety old Ambassador taxi, people seemed angry with Rajiv Gandhi. They felt betrayed. The Bofors scandal had destroyed his reputation. The allegations were straightforward and serious: that a coterie around Rajiv Gandhi had taken bribes to approve the purchase of the Swedish Bofors gun. Some even accused Rajiv Gandhi of being personally involved. His family friendship with Ottavio Quatrochi, a wheeler and dealer from Italy (the country where Sonia Gandhi was born) didn’t help matters. The Bofors scam hit the headlines in 1987 and the fall from grace was swift. The Congress under Rajiv Gandhi was delivered a thundering slap by the Indian voter in the 1989 Lok Sabha elections, coming down from a 400 plus tally to less than 200.

Congress supporters and sympathisers still think that had he not been brutally assassinated on May 21, 1991 by an LTTE suicide bomber, Rajiv Gandhi would have learnt his lessons, revived the Congress and led India towards the 21st century. The author is not sure. He recalls the 1991 Lok Sabha election campaign and there were clear signs emerging from “field” visits that a Congress majority in 1991 was not a certainty. There was a mini sympathy wave after his assassination in the multi-phase elections and the Congress won 236 seats, well short of the majority mark of 272.

He remains a paradox. Rajiv Gandhi loved interacting with the media and was known for his witty repartee. For instance, during his official visit to the United States in 1985, he had floored the journalists while answering a potentially troublesome question about Khalistan and Pakistani support for it. Gandhi had quipped that backers of Khalistan should not forget that the capital of the original Sikh Empire was Lahore! Yet, it was his regime that harassed and hounded The Indian Express for exposing “corruption” in the government. His government even introduced a Bill in Parliament to curb media freedoms; only to back out after strong protests. He appeared unfailingly polite on most occasions. And yet, Rajiv Gandhi publicly asked the then Foreign Secretary A. P. Venkateshwaran during a press conference in the most graceless manner.

His regime took many bold steps. The Panchayati Raj Bills made into law were one instance. The Consumer Protection Act was another. The anti-dowry law was yet another. There were many more. But his fatal mistakes were political. Rajiv Gandhi was at the peak of his popularity after delivering that historic Congress centenary speech in December 1985. And then he committed political hara kiri. The Supreme Court had delivered a historic verdict that provided alimony to Shah Bano, a divorced Muslim woman from Madhya Pradesh and stated clearly that all divorced Muslim women were entitled to alimony as a right.

Conservative and obscurantist sections of the Muslim community protested against the verdict. A large number of progressive Muslims supported the SC verdict. Yet, Rajiv Gandhi rammed down a law using his brute majority to negate the SC verdict. This gave ammunition to the BJP which openly accused Rajiv Gandhi of “Muslim appeasement”. The allegation struck a chord. To negate that, his regime allowed the locked doors of the disputed Babri Masjid-Ram Temple to be opened for Hindu devotees. The two decisions effectively sealed the fate of Rajiv Gandhi and the Congress. The accompanying chart makes it clear how relentless the decline of the Congress has been since those heady days.

By 1991, Mandir and Mandal had completely taken over politics in the Hindi heartland. The author is quite sure Rajiv Gandhi simply did not have the political skills to handle these transformative changes. So yes, it is nice to remember him with nostalgia. But foolish to think he could have revived the Congress.

(Author has been a media professional for over 3 decades. He is now Executive Director, C Voter Foundation. Views are Personal)