Sutanu Guru

Back in 1977, the then school going author and his family were tenants at 17, Satya Nagar in Bhubaneswar. The house belonged to the late Dr. Manmath Nath Das, the well-known historian who went on to represent the Congress in the Rajya Sabha. In April, the author’s aunt got married and since the groom was from Puri, the marriage was organized at 17 Satya Nagar.

The author doesn’t recall the exact number; but at least 60 first and second cousins had gathered for the festivities. Everyone pitched in with either some volunteer work or a lot of unsolicited advice. Gossip about absent cousins was rampant. Groups played the card game 29 till late into the night.

There simply was not enough bed space. So only the elderly got to sleep in beds while the rest sprawled on mattresses spread on the floor. There was something magical about that noisy, boisterous, gossip filled festive gathering. In most middle-class urban families, such gatherings of cousins are fast becoming a relic of an era gone by. Except in rare cases, the concept of joint families has virtually disappeared from urban India.

If you go by the kinds of idiotic TV serials unleashed upon Indians by the likes of Ekta Kapoor, joint families are a den of vile conspiracies where siblings and cousins plot against each other. There is that in some joint families. Usually, the disputes, fights and conspiracies revolve around property, particularly when it is not properly divided.

Yet, families have remained the greatest and most powerful social institution in India for centuries. In the era rapidly disappearing, siblings and cousins were the greatest support systems in times of trouble. Cousins were always there to dance during festivities. It was routine for them to gather at one place during the summer vacation and spend weeks just goofing around. Forget internet and smart phones; since even TV was not around when the author was growing up, there was a lot of genuine interpersonal interaction and a lot of physical activity that passed as entertainment.

The author still fondly remembers a Dussehra gathering at his maternal grandfather’s village near Sambalpur in 1980 or so. Siblings, first and second cousins were abundant. There were four of them younger than the author who were technically his aunts and uncles. That’s unheard of in contemporary urban India. That Dussehra, the author and cousins used to wake up at the crack of dawn to watch post harvesting work, play with each other in mounds of straw and rush of to a nearby stream to wash off the itchiness caused by straw.

The author simply cannot envisage a future where the next generation siblings and cousins would spend such magical holidays. Of course, thanks to rising economic prosperity, they enjoy holidays in Europe and other exotic locations. It is wonderful. But as good as the magical holidays spent with cousins?

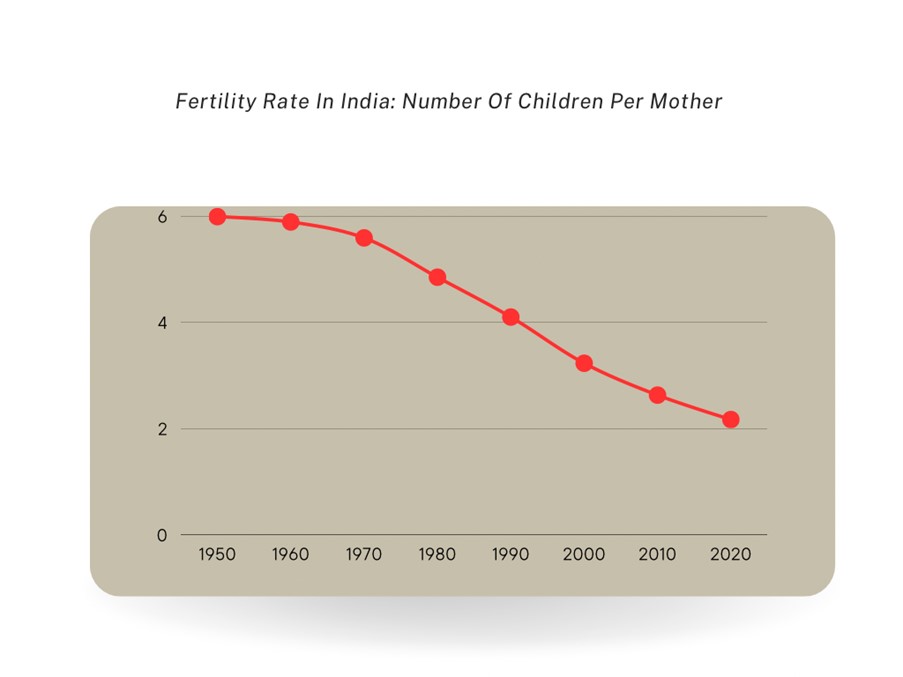

That era is permanently gone. The reason is very simple. Parents no longer have many children who would in turn generate cousins. From the mother’s side, the author has 12 cousins. Together, the author and his three siblings-all above 50 now-have five children. The bonding is still there. But how intense will it remain when these kids have their own children in the future?

In fact, it is now common for urban middle class parents to have just one child. So where then is the question of sibling bonding and large family gatherings with cousins? Our youngest sibling who is in the armed forces has one daughter who is at Stanford pursuing her graduation on a scholarship. Some bonding with her four cousins will continue if she comes back to India. But what if she doesn’t? What about the generation after her?

The second reason for the fading era of cousins is urbanisation, work patterns and lifestyles. You can still find large families in many villages, all living under one roof. The sheer cost of real estate in urban India means most families (usually nuclear) live in flats. Besides, changes in the economy mean that work pressure for middle class Indians is intense. Both husband and wife work long hours. Where is the time left to spend and bond with cousins?

Finally, the arrival of the digital world means that almost everyone is glued to their smartphones, tablets or some other personal gadget during free time.

Change is inevitable. Usually, it is for good. But as they say in economics, there is an opportunity cost for everything. Indian families are becoming more prosperous. But that prosperity is also denying them the age-old magic of just goofing around with siblings and cousins.

(Author has been a media professional for over 3 decades. He is now Executive Director, C Voter Foundation. Views are Personal)