Sanjoy Patnaik

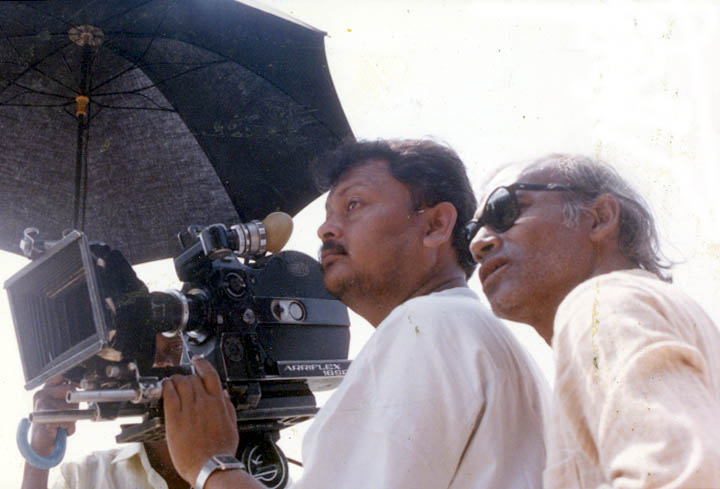

Winter 1975, it was December; when Manmohan Mohapatra was making his debut film ‘Seeta Raati’ (Winter Night). That is when I first saw a young Raju Mishra, an FTII cinematography student, in his mid-20s. As a nine year old, I remember a strikingly irritable-faced fair complexioned man with perennially twisted eyebrows that were partly covered by his trademark beige coloured cord cap. One evening during the shoot; as a child artist then, I was struggling with my dhoti, which was for some reason falling down every time I fixed it.

I requested the young man standing next to me to fix my dhoti well, confusing him to be a member of the costume crew. To be honest, I was close to being impolite, constantly distracted from remembering my lines because of my falling dhoti. Much to my discomfort, I sensed an unnerving quiet around me with people closely watching the dhoti-fixing episode. Everyone around was completely sure that this short tempered young man would for sure greet me with a tight slap. By contrast to the expectations of people around, his response was just the reverse. He quietly fixed my dhoti, and smiled; a smile that announced the onset of a long standing relationship. My last conversation with Raju Sir was towards the end of 2019 when he said to me; ‘come over sometime, and we will watch my new film together – for all you know this might be my last film’. We planned a meeting that never happened!

E Jibana Maane Nuhen Aaaha

Mid-70s and later, the Odia film industry saw a host of new faces oozing with talent – Sriram Panda, Bijay Mohanty, Mahasweta Ray and Ajit Das; most of who continue to be household names in Odisha. The most striking common aspect of these actors was that they hailed from small towns like Nabarangpur, Baripada or Puri and not Cuttack, which by then was the epicentre for film making in Odisha. Towards the end of 70s; entered Raju Mishra, an immensely talented FTII graduate from a small urban centre called Jatni and made a royal announcement of his presence with the astounding success of his rather unconventional film, Ulka, that continues to be a reference film in Odisha with its midas touch of modernity, addressing the struggles of the youth of 70’s; not to beat the enchanting melodies widely in circulation within the youth even today.

Ulka was a trend setter in a number of ways and only Raju Mishra, the rebel he was, could have had the guts to deviate from the established genre even in his first film. He had the courage and creative genius to deviate from the established melodramatic pattern of storytelling that was largely confined to family drama. With Ulka, Odia filmmaking shifted from the rural milieu to urban space projecting the existential crisis that the post-emergency youth faced. The soul of the film was its music! What made its music immortal was the creative sense of ‘using the pause’ and the less used mouthorgan that was largely representative of fun and youthful exuberance.

Abhimanini Mun Amania Dheu

Mesmerised by Ulka till today, there were many like me who felt that Ulka was as a film well ahead of its time. In many senses it raised the bar of film making in Odisha. There was another half that could not accept the paradigm shift that Ulka introduced, both socially and cinematically. Ulka was a box-office failure that left the producer bankrupt; and Raju Mishra without any new films for some years. But its creative success taught that ‘experiments and change are mandatory for growth’, a risk that he was ready to take even in his debut film.

Ulka continued to be the most sensitive spot in his heart and a passionate discussion on Ulka always left him vulnerable and lonely. While with Ulka he brought in a breath of fresh air and a wave of new thinking into film making, he also created a set of enemies who were largely a group of insecure film makers united to pull him down.

In an intense conversation during the making of Rupa Gaon Ra Suna Kaniain (1994), he confessed that Ulka still haunts him. He said; ‘I had invested my soul in Ulka, leave alone my destiny’. He continued, ‘financial return is key to film making since that keeps the wheel rolling but I prefer not to remember the financial loss from Ulka; I rather forget them. I didn’t get a single film offer because of that box office failure. But Ulka gave me a lot – a name as a ‘different’ filmmaker and a state award for the Best Cinematographer.

Those were days when I was financially insecure. I decided to go and receive the award at a state level function at Rabindra Mandap which carried a cash prize of Rs 2000.That evening, after the event when I boarded the train back to Jatni; I couldn’t resist the temptation of opening the envelope. That came as a big surprise. The envelope contained 1500 rupees while the cover mentioned 2000. I kept counting the crisp fifteen 100 rupee notes and continue to ask myself till now; who could have taken the remaining five. The pain of losing 500 rupees was more than the pride of being the Best Cinematographer. An artist was robbed! By the time I reached Jatni, I had told myself that I will ‘create a new culture’ in an environment which robs, humiliates and ridicules artists. I did my bit. I dared’.

People who worked with him including his adversaries thought he was a great cinematographer. Personally, I always thought he was a magician, a visionary and a master craftsman. He was a teacher par excellence. He was known for his trademark ‘irritation’. But not many probably knew that this irritation was not personal, it was his response to the rampant mediocrity that one is surrounded by.

Maa Tume Mamatara Simahina Sagara

A good number of Odia artists, trained professionally on film making or dramatics invariably prefer to return to Odisha with the avowed objective of contributing toits rich cultural heritage; knowing very well about the limited opportunities, the insignificant and scanty respect given to artists in Odisha and that financial returns which is miniscule. Yet none can question their commitment, their junoon of home coming and doing something in their own state, in their own language and for their own people. Raju Mishra being a crafty cinematographer could have earned more fame and money had he opted to settle down in Mumbai after FTII. But the dream of Ulka with a shoestring budget bears ample testimony of his commitment to good cinema, more importantly, contributing to the growth of a small film industry like Odisha.

The situation, however, has changed in the last one decade. With shrinking film making opportunities, professionally trained Odia artists and technicians today, hardly want to come back to Odisha. Last year, a fresh FTII pass out told me that ‘dreaming of making Odia films could be suicidal and I don’t want to become a victim of the UBO syndrome. Sorry, UBO means ‘Unfortunately Born in Odisha’, he explained. I didn’t disagree.

Magicians like Raju Mishra are not born every day. Odisha has lost one more chance to benefit from his creative genius. When an artist dies in Odisha, the media writes, ‘a great loss to the state’. Does this mean anything to anybody? Honestly, how is Raju Mishra’s death a great loss to the state, apart from it being an irreparable loss for the family and people like us who knew him? Was Raju Mishra’s skills and talent used anywhere when he was alive, especially after 2013 when he was awarded with the Jayadev Samman? With state’s weak cultural agenda and priorities, artists are largely unwanted creatures in Odisha.

Sir, you will be missed when we dream of cinema, when we look through the lens; your endless ‘scolding’ will motivate us to do something that is not mediocre and ordinary. Rest in Peace.

(Author is a Development Professional and Film Maker)