Pradeep Kumar Panda

India slipped 10 ranks in the Global Democracy Index 2019 recently published by the Economist Intelligence Unit, and retained its status as a “flawed democracy”. India was ranked 51 on the index for 2019 – its lowest since the rankings began in 2006.

India’s overall score fell from 7.23 out of 10 in 2018 to 6.90 last year, mainly due to an “erosion of civil liberties”, the index report said. The country was ranked 42 in 2017 and 41 in 2018.

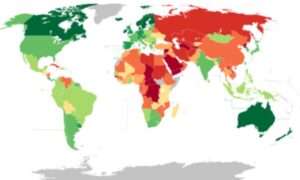

According to Economist Intelligence Unit, the Global Democracy Index is based on five categories: electoral process and pluralism, civil liberties, the functioning of government, political participation and political culture. The index ranks countries based on their scores on 60 indicators, and then classifies them as one of four types of regime: full democracy, flawed democracy, hybrid regime and authoritarian regime.

Last year’s index studied political systems across 165 countries and two territories. The Economist Intelligence Unit said the year 2019 was the worst for democracies since 2006, with the average global score falling to 5.44 out of 10 from 5.48 in the preceding year.

Last year’s index studied political systems across 165 countries and two territories. The Economist Intelligence Unit said the year 2019 was the worst for democracies since 2006, with the average global score falling to 5.44 out of 10 from 5.48 in the preceding year.

Only 22 countries, with a combined population of 430 million, were classified as “full democracies” in 2019, while more than a third of the world’s population were found to be living under authoritarian rule. The list was topped by Norway, while North Korea was at the bottom.

The global decline was driven mainly by regions such as Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, West Asia and North Africa. Most Asian countries declined in the rankings in a “tumultuous” year that saw various protests and government restrictions on freedom.

The twelfth edition of the Democracy Index finds that the average global score has fallen from 5.48 in 2018, to 5.44. This is the worst average global score since The Economist Intelligence Unit first produced the Democracy Index in 2006.

Driven by sharp regressions in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, four out of the five categories that make up the global average score have deteriorated. Although there were some dramatic downturns in the scores of certain countries, others have bucked the overall trend and registered impressive improvements.

As reflected in the improved average global score in the political participation category in 2019, there was a major increase in political protest and social unrest in emerging-market regions of the world. This was the biggest upsurge of protest since 2014, in the aftermath of the global economic and financial crisis.

As then, the 2019 protests varied in nature by country and context, but there were several common underlying drivers. The sheer number of protests spanning different time zones has caught the attention of commentators everywhere. In fact, protests have been building a head of steam for several years. The backdrop to the recent wave of protest is in part economic (austerity, cost-of-living increases, unemployment, income inequality).

But economic issues alone cannot explain the upsurge of unrest. Regressive democratic trends and political failures have been major factors. It is the growth of popular distrust in governments, institutions, parties and politicians that is driving many of today’s protest movements. In the developed world, increasing political participation has been driven by similar concerns about the inadequacies of democratic politics.

Dissatisfaction with the mainstream political parties has given rise to new populist parties and a demand for more direct democracy. In many places, scores for voter turnout have increased, membership of political parties and organisations has grown, and engagement with politics has improved.

Despite disenchantment with democracy, and probably because of the degree of disaffection that now prevails, populations are turning out to vote and to protest. This heightened level of popular engagement prevented the Democracy Index from sliding even further than it did in 2019.

There was little change at the very top and the very bottom of the index. Once again Norway came out on top, with a score of 9.87 (on a scale of 0-10), and North Korea was at the bottom of the global rankings, with a score of 1.08.

Some of the more notable moves up and down the rankings were recorded by Thailand, which registered the biggest improvement in score and ranking, and by China, which registered the greatest decline. Following the first election since the military coup in 2014, Thailand’s score improved by 1.69 points and it moved up 38 places in the rankings, from a “hybrid Democracy” to a “flawed democracy”. China’s regression resulted in a decline in score of 1.06 points and a fall of 23 places down the rankings.

Although there was no big movement at the top and bottom of the index, there were big movements in the rankings elsewhere. Three countries (Chile, France and Portugal) moved from the “flawed democracy” to the “full democracy” category. Malta moved in the opposite direction, falling out of the “full democracy” category to become a “flawed democracy”.

At the other end of the democracy spectrum, Iraq and Palestine moved from being classified as “hybrid regimes” to “authoritarian regimes”. Algeria moved from being an “authoritarian regime” to a “hybrid regime”. El Salvador and Thailand moved out of the “hybrid regime” category into the “flawed democracy” category, while Senegal moved in the opposite direction from a “flawed democracy” to a “hybrid regime”.

There were other notable improvements, including in Armenia, Bangladesh, El Salvador, eSwatini, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Sudan, Togo, Tunisia and Ukraine, and there were regressions in Belarus, Benin, Bolivia, Cameroon, Comoros, Egypt, India, Guyana, Singapore, Mali and Zambia. An overall setback in Latin America, despite some gains Latin America is the most democratic emerging-market region in the world.

However, its overall score fell substantially in 2019, from 6.24 in 2018 to 6.13, a fourth consecutive year of decline. In 2019 the regional decline was chiefly driven by the post-electoral crisis in Bolivia, and to a lesser extent by the democratic regression in Guatemala and Haiti. Overall scores fell in close to one-half of the countries in the region. That said, the only two regional ranking modifications in the 2019 Democracy Index were both upgrades (Chile and El Salvador).

The growing use of authoritarian practices in Venezuela, Nicaragua and Bolivia accounts for much of the recent regional democratic deterioration.

Asia: a year of drama and tumult Asian democracies had a tumultuous year in 2019. The biggest score change occurred in Thailand, whose score improved by 1.69 points compared with 2018, to 6.32, resulting in a rise of 38 places in the global rankings and a transition from a “hybrid regime” to a “flawed democracy”. The introduction of a “fake news” law in Singapore led to a deterioration in the score for civil liberties in the city-state.

China’s score fell to 2.26, and the country is now ranked 153rd, close to the bottom of the global rankings, as discrimination against minorities, especially in the north-western region of Xinjiang, intensified and digital surveillance of the population continued apace.

Hong Kong slipped a further three places in 2019, from 73rdto joint 75thwith Singapore out of 167 countries, amid a deterioration in political stability following a sizeable cumulative decline in 2015-18. The wave of often violent protests that grew from mid-2019 is largely a manifestation of pre-existing deficiencies in Hong Kong’s democratic environment.

This is not a good sign for India. Republic Day is round the corner. The whole essence of democracy is constitution which ensures free speech and freedom of expression. These should not be curtailed. There should be conducive atmosphere for autonomy of all citizens.

(The author is a New Delhi based Economist)