Kailash Chandra Dash

Maritime trade which was responsible for enriching the Odias in the early and medieval period is a significant aspect of the study of the socio-economic history of Odisha. Overseas trade is an important element of the Odia traditional accounts. Archaeological remains in Odisha, as well as the vast literary texts of the early and medieval phase, provide the evidence on the spectacular maritime activities of the merchants of Odisha. A close study of the art and the architectural remains of Odisha also provide an interesting linkage of the people of Odisha in early medieval phase with the different regions of the world.

The folklore and popular sayings about the sea voyages of the merchants of Odisha in the past have been presented by the nationalist historians in the first phase of the 20th century A.D. The Odia Mahabharata of Sarala Das in the 15th-16th century A.D.,Prastava Sindhu of the poet Dinakrishna Das and many other Odia literary texts of the late medieval period provide unmistakable evidence on the maritime trade and the shipbuilding activities in early and medieval phase. The festivals and fasts of the Odia people also contain an interesting account of the shipping activities of the ancient Odia merchants. Numerous references to sea-voyages can be found in the stories and tales that have come down to us from antiquity. According to one traditional account, the merchant`s son is setting out for the sea, his ship lying at anchor is worshipped or rather honored by the ladies of the household. The merchant`s son after undergoing various trials and adventures in the course of his voyage comes home at least with a lot of treasures. Occasionally he forgets his married life and his relations at home and marries a princess in a foreign land. His faithful wife pines away and suffer untold miseries. She gets her husband back again by the power of her prayers and as a legitimate reward for the devotion to her lord. These tales are the common property of all nations and yet the maritime greatness of the Odias can be detected from such tales. The Bratas or the semi-religious observances which have passed into the bone and marrow of the people are of a more substantial nature and afford more reliable proofs of sea-voyages. Unmarried girls of all castes to this day perform a Brata called Khudurukuni Osa on Sundays in the month of Bhadra. The brata is in honor of Goddess Mangala who fulfils all desires. In the story portion of the worship, there is a pathetic tale of Tapoi,the daughter of a merchant. The prevalence of the story throughout Odisha and its incorporation in the worship of unmarried girls show that sea voyages were at one time a common aspect in the land. There is no such bratakatha in the worship of unmarried girls in Bengal. The worship was well known in the late medieval period. It is also customary in every household in Odisha to paint with fine rice dust(Muruja) or rice paste an image of a sailing ship in the inner courtyard of the house in Dewali night. Early in the morning of the next day the ladies put all useful articles i.e. boxes of every description,utensils,pedis or cane boxes inside the image of the ship and make their bandapana or obeisance to it. In days gone by, all sailing ships used to leave the foreign ports the day after Dewali in the month of Karttika and ladies used to make their bandapana to the ships before they started. They waved lights before them, blew their conchshells before the ships. The sea voyages have long been abandoned and people now-a-days cannot see a sailing ship on their behalf. Fishing crafts and ferry boats are all that can be seen now in the rivers and sea-coasts of Odisha. But the old idea that sea voyages and overseas trade brought wealth to the family still persists and ladies now-a-days make their bandapanas to the painted image of a sailing ship in their own courtyard on the day the ships used to start for their voyages. The belief that the performance of this ceremony ensures wealth and plenty to the family shows the hold that sea voyages had on the people of Odisha in by-gone days. When a ship came back after finishing its voyage the ladies of the household hurried to it and performed their usual bandapanas before the men and cargo disembarked on the shore. The day of starting was fixed; but there was no fixity of the day of return which varied according to the nature of business that the ships had to in its particular voyage. Consequently the bandapana after return could not be reduced into a semi-religious ceremony in which the fixity of the date itself was always an essential factor. Sailing ships in those days started the day after Diwali in the month of Karttika when the South Western Monsoon Waves (Dakshina Pashchima Mausumi Vayu) leaves the Bay of Bengal. Its place is filled up by the North Eastern Monsoon Waves (Uttara-Purva Mausumi Vayu). This month was favourable for ship voyage to the south. The waves have changed their motion after crossing Vishuva Rekha. Hence the Odishan ships move to north-west instead of north-east and the direction is towards the South East Asian countries. The sailing ships in those days completed their journey by the end of Chaita. It was not safe for a sailing ship to breast the high waves and storms that rage in early summer and the rainy season. Such a ceremony is not observed in any part of Bengal. Its observance in Odisha continuously is a definite proof of the maritime activity of the Odias in days past. The sky-lamp(akasha dipa) which is lighted in the month of Karttika by the ladies in Odisha is an indication of good will for the sailing ships of the Odishan merchants. They were in days past called bidaya bati(Farewell lamps) for the Odishan merchants sailing in the high seas. On Karttika Purnima day colourful handmade boats are floated on the tanks and rivers by the Odias and this observance is a recollection of the maritime activities of the Odishan merchants of the past.

The kaibarttas or Kewats of Odisha form an interesting part of the Odia maritime tradition. They inhabit in large numbers on the entire sea-board from the river Suvarnarekha to Puri. A section of Kewats is called Boitial Kewats whose occupation is that of sailors in sea-going vessels, the word Boita being invariably used for sea-going ships. The caste legend of the Kewats throws a good deal of light on their occupation as sailors in sea-going vessels. The full moon of the month of Chaitra was a great day of the Kewats. The full moon of the month of Chaitra was about the time when sea voyages became very dangerous and all sailing ships used to return home. The Chaitra full moon was thus the beginning of a few months of happy leisure after the cares and worries in the sea. The Kewats still celebrate this occasion for the puja of the ship. A Brahmin priest is called to perform the worship of the ship on that occasion. The root mantra used on the occasion has in it the root mantra of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and plenty. The very tenor of the worship goes to show that the people in days past understood the intimate connection of sea voyages and overseas trade with good fortune. Apart from this annual worship the goddess Mangala is believed to reside permanently at the prow of a sailing ship which is always kept clean by the sailors whether the ship is sailing ,anchoring at the harbour or is out on the high sea. Her function is to save the ship from the perils of the sea. In all sea-going ships of early period it was customary to keep a lamp burning at the prow in honour of Mangala. If she was pleased with the conduct of the sailors, the ships, it was believed, would not collide with a sunken hill or a treacherous sand bar. If by any chance she was angry with the sailors, the ship was sure to come to grief. There was actually no image of Mangala at the prow of the ship, not even a symbolical representation by a ghata or an earthen pot. The sign of Swastika or good luck painted in red vermillion at the prow was the symbol of the goddess.There was always a greater danger at the prow of a sailing ship than at the other end and superstition naturally assigned the goddess Mangala a permanent seat there who saw to the safety of the ship more than the sailors themselves with their frail owners of observation.

The Odia poet Sarala Das in the Sabha Parva section of his Mahabharata refers to kaivarta Nrupati (chief of the Kaibartas) in connection with the making of Suvarna Boita. It indicates that in days past the Odishan ships(Boitas) had proceeded towards South East Asian lands(Suvarna Bhumi).In the pre-Sarala Das phase(before 15th century A.D) there were places in coastal Odisha which were associated with boat or ship making. The existence of boita Kudas near the sea-shore areas of Odisha confirms our suggestion. Temples and shrines on the sea port areas from Tamralipti to Chilka contain many traditional accounts relating to the sea-faring enterprise of the Odias. The history of the ancient shrine of Varga Bhima, a goddess standing on Siva with four hands like Kali in the Tamralipti zone is associated with a sea-going merchant of fame who is still sung in popular ballads. In north Balasore near about Mirgada the shrine of Lankeswari is associated with maritime pride. The lower portion of her body is buried in sand. Mariners who passed this coast by ships promised pujas to her on their safe return home and some of them touched the shore and offered puja to her to ensure a prosperous voyage. The temple of Gada-Naikani in Balramgarhi at the meeting spot of Burabalanga and the sea and the Mangala temple at Kakatpur in Puri district were well connected with Odishan seafaring activities. The shrine of Digavarini near Chitrotpala zone in the present district of Jagatsinghpur is an interesting seat of maritime trade.

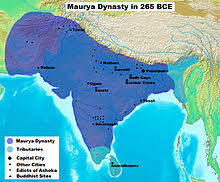

From the phase of the establishment of the Maurya rule in India in 4th century B.C. till 14-15th century A.D. Kalinga was considered as an important maritime kingdom which had seafaring activities. The illustrious Maurya king Ashoka could not tolerate the maritime supremacy of Kalinga for which he had to wage a bloody war. Lama Taranath,a Tibetan historian,could appreciate this economic aspect of the Kalinga war of the Maurya king Ashoka when he stated that the Nagas had stolen away the jewels from Ashoka at which the emperor became angry and conquered the territory of the nagas. Eggermont has been inclined to identify the Nagas with the sea-faring people of Kalinga and the conquest of their territory has been explained by him as the conquest of Kalinga. It is possible to speculate that for some years the independence enjoyed by the Kalingan merchants in the whole bed of the Eastern Sea coast was gone and under Mauryan supervision the Kalingan oceanic routes were occupied by others. But in the post-Mauryan period there was a spectacular rise of Kalinga as a maritime power from the period of Mahameghavahana Kharavela. A tradition recorded in the Rajabhoga of Madalapanji refers to Bhoja as a king of Odisha and he was associated with maritime activities.Odia historian Narayana Tripathy has identified this Bhojaraja of the Madalapanji with king Kharavela. Although more reliable evidences are not with us to testify the veracity of the statement of Tripathy we cannot deny the possibility of his support to revive the maritime activities of the merchants of Kalinga which had received considerable set-back during the Maurya rule. We have only one record like the Hatigumpha inscription which describes a part of the life and achievements of Kharavela and it describes the maritime significance of Kalinga before Kharavela. After the discovery of other evidences about the great king we can have detailed information about the economic activities of his period. However from the reign of Kharavela Kalinga witnessed a real grand phase of maritime trade which began to languish only in the later medieval period.

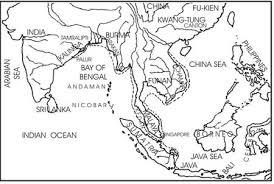

From the beginning of the Christian era till the end of the Somavamsi period before 12th century A.D. there started intense maritime activities of the Odishan merchants. It led to the establishment of trading centres and colonisation in the Far east and Malayesia. Different ports became active during this phase. The Geographike Huphegesis of Ptolemy refers to Palaura(located in Ganjam district) and the mouth of the river Manada(Mahanadi) as the important zones of maritime activities. It is also supported by Periplus tes Exo Thalasses, compiled by Marcianus of Heraclea(A.D. 250-500) which states about Apheterion as a place from which all those navigating to Khryse leave. The term Khryse denotes different parts of South East Asia like Khryse Nesos(Suvarna dvipa), Khryse Khora(Suvarnabhumi) and Khryse Khersonesus. These areas have now been identified with the modern states of Sumatra,Java,Indonesia,Thaton and Pegu in Burma and parts of Malay peninsula. As stated by Marcianus one of the main points of departure from India for ships bound for South East Asia was located on near the coast of Southern Odisha in the early centuries of the Christian era. Manikyapatana was another important trading centre of early and medieval Odisha. It is within the zone of Chilka and is now included in the Brahmagiri zone. An excavation conducted by Odisha institute of Maritime and South East Asian Studies(located at Bhubaneswar) reveals the existence of a port in the area of Manikyapatna in ancient time. The arechaeological excavation has brought to light rouletted ware fragments of amphora etc.indicating contact with Roman empire in the early centuries of the Christian era. The discovery of Celadone ware indicates trade contact of this zone with China. Hence the people of this region had an important link with overseas trade and commerce.

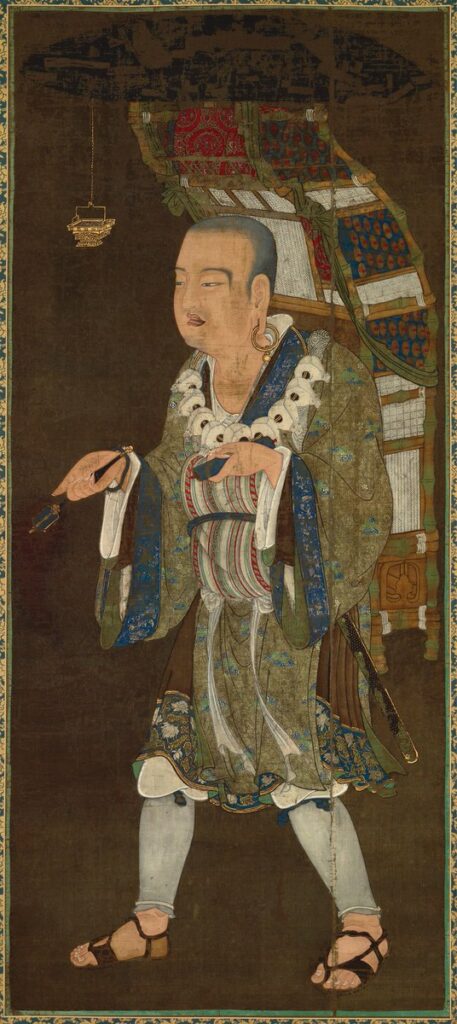

Important ports on the coasts of Kalinga and Utkala in the early phase were Tamralipti,Chelitalo and Palaura. Hiuen Tsang(Xuanzang) ,the famous Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, refers to the city of Chelitalo(Zhe-li-dalo) near the sea shore in Odra which was a thoroughfare and resting place for sea-going traders and strangers from the distant lands. It has been identified by A.Cunningham with Charitrapura and according to him it was identical with the present town of Puri. Waddel identified it with Nendra on the bank of Chitrotpala, a tributary of the river Mahanadi in the district of Kendrapara. A.P.Pattnaik identied it with Chhatragarh near Chilka zone. The most important point for identification of this port has been given by H.P.Ray who states that it is identical with Chilika tala. Ray states; I think dalo is tala which means lake in India. In that case Zheli may perhaps represent Chili of Chilka in which case the word will be Chilika tala( the lake Chilka). This interpretation can now be rejected by the following arguments.

During the visit of Xuan zang in the 7th century A.D. Chilka zone was not within Odra country and it was then in Kongoda. (Behera 1982:13-24).The Chinese pilgrim has stated about Zheli-dalo in connection with Odra. Interestingly the same pilgrim also refers to the geographical location of Kongoda after Odra. Hence Zheli-dalo cannot be located in Chilka zone.

According to Ray Zheli-dalo is the Chinese rendering of Chilka tala.In the 7th century A.D. the name of the place was definitely not Chilka. Chilka appears to be used after 14th century A.D.. An inscription of Narasimha temple in the inner compound of Jagannath temple of the period of Chodaganga of the Ganga dynasty(12th century A.D.) refers to Chilka zone as Jalakhanda Visaya in which was situated the village Maluda. The composer of the verses of the inscription refers to Maluda of the Chilka zone which is still well known. But he does not refer to Chilka which is described in another name called Jalakhanda Visaya. It indicates that even in the 12th century A.D. the name of Chilka was not applicable to that zone. There is a reference to Chilka in a palm-leaf manuscript entitled Brahmanda Purana which was found in a house of Brahmin in Bhubaneswar and this reference tempted late Birupakshya Kar and Radhacharan Panda to locate Chilka in the 10th and 11th century A.D. This manuscript was collected from the house of Madhusudan Mishra of Bhubaneswar and it was believed to have been compiled between A.D.1568-1600. The verse referring to Chilka in Brahmanda Purana of Bhubaneswar was interpolated as the verse has not been stated in any other manuscript of Brahmanda Purana. Thus the reference to Chilka in the Bhubaneswar manuscript can be datable to 16th century when the term was well known in Odisha. Therefore Chilka as the name of the zone was unknown in Odisha during the time of the Chinese pilgrim.

The Chinese rendering of the term as Charitrapura has not been totally rejected by H.P.Ray. According to Ray this identification is tenuous. In fact the port indicated by the Chinese pilgrim might have lost its name in the medieval period. Its disappearance due to some unknown reasons leads to the difficulty of its exact location. On the other hand the term may indicate Charitra or Chitra and it can be located within the Odra zone which during the time of the Chinese pilgrim did not extend upto Chilka zone. The port has to be located somewhere in the Konarka-Kuruma zone near Chitrotpala adjacent to the sea.In local language Chitrotpala is also called Chiteratala which was used by the Chinese pilgrim as Chelitalo

There were many other maritime zones in Odisha in early and medieval phase. Khalkattapatna in Puri district has been excavated by the Excavation Branch-IV of the Archaeological Survey of India. It was situated 11 kms.east of Konarka and is located on the left bank of the river Kusabhadra which falls into the Bay of Bengal 3 kms. to the north east. Excavations at Khalkattapatna(1984) revealed a brick jelly floor which might have served as loading-unloading platform. Pottery recovered from the excavations consisted of Chinese celadon ware, Chinese porcelain with blue floral designs on white background, egg white glazed ware and glazed chacolate ware all of the Arabian origin. The most important finds from excavations were fragmentary Chinese circular copper coins datable to 14th century A.D. This indicates the existence of a port in this zone in early phase.

Two other important maritime zones were Simhapura and Dantapura. Dantapura as a trading zone was a celeberated centre for danta (the tusks of elephants) and the centre has to be located somewhere in the Ganjam-Vishakhapatnam area. Odisha in the early phase was a famous centre for manufacturing and selling of the hasti-dantas. (Ibid.) The popularity of hasti-danta(teeth of elephants) in Kalinga in the early medieval phase has also been stated in the account of the Arabian merchant Sulaiman whose account entitled Salsilatu-t Tawarikh of A.D.851 refers to the elephant teeth in Kiranj or Kalinga. The location of Simhapura of the Ceylonese tradition on the sea-coast of Odisha has to be decided in order to find an interesting link of the maritime activities of the Kalinga merchants of the pre-Ashokan phase. There are abundant evidences regarding the emergence of Kalingan settlements in the South East Asian countries in early times. There were many factors which led to the expansion of Kalingan culture across the seas. The ports of Kalinga had opened different sea routes to different lands for seafaring trade. The adventurous mariners continued to have commercial, socio-cultural and political relations with South East Asian countries.

The sculptural decoration in early and medieval Odisha definitely refer to the contact of the Odishan merchants with the lands beyond the seas. A study of the art of the Khandagiri-Udayagiri caves reveals the use of West Asian decorative elements such as honey suckle, acanthus, stepped merons, winged animals etc. Some of the pilasters facing the doorways of the cave of Anantagumpha have ghata-bases ornamented in the Hellenistic fashion, very similar in treatment to vessels found from excavations in Western India. A yavana guard is shown on the left pilaster of the cave in the upper storey of the Rani gumpha. The kilted foreigner is in boots and wears a fillet on the forehead, while a sheathed sword hangs from the left side. The huge Bell Capital from Bhubaneswar imitated from Ashoka columns also shows West Asian motifs in its ornamentation. Representations of boats in the temple art of Odisha, as at Bhubaneswar, Puri and Konarka indicate the importance attached to water transport. Comparative studies of Buddhist art of Odisha with that in South-east Asia show several common elements and striking affinities. The Buddha heads from Ratnagiri, Lalitagiri and Udayagiri and those from central Java share common traits of massive form, sensitive modelling and spiritual expressions. The Javanese Boddhisattvas from Chandi Mendut have their attributes placed on long lotuses in the style distinctive of the Lalitigiri figures of Orissa. The representation of Jiraffe,an African animal in the temple art of Konarka suggests contact with Arab merchants who might have been commissioned to bring this animal from Africa to the eastern coast. It is interesting to note that an ivory comb(dated between Ist-3rd century A.D.) has been recovered from Chansen in Central Thailand. The Srivatsa motif on it is analogous to the motif found in the art of Khandagiri, Udayagiri caves. later on Srivatsa motif became fairly common in coins from OCEO in Vietnam at Arakan.

Between 2nd and 4th centuries A.D.Odisha had direct maritime contact with South-east Asia. The importance given to sea trade with South-east Asia was partly the result of the extension of the inland and inter-regional trade and commerce and predominantly the outcome of the rising demand in the West for spices. It is likely that the Odishan middlemen merchants took advantage of this situation and involved themselves in the spices trade, especially the trade in cloves.The existence of an Apheterion, point of departure to South-east Asia must have facilitated voyages to South-east Asia for trade in ivory and cloves. Odishan trade seems to have declined in the post-Gupta period, although cultural contacts with other countries such as Sri Lanka,China,Indochina etc.continued. Again the active role of Odisha in the maritime trade is witnessed from the 11th to 14th century A.D. The material evidence from the excavations of Manikpatna adds considerably to our understanding of the overseas contacts of Odisha in the medieval period. Sila Tripati has pointed out some probable natural causes for the decline of ancient ports of Odisha. Natural factors like tectonic movement, coastal sedimentation, development of sand dunes in the navigational channels, change of river course, flood, cyclone, sea level fluctuations etc. played a crucial role for taking away the erstwhile commercial advantages of ancient Kalingan ports and towns. Despite that the sailors, merchants and traders of Kalinga in early and medieval period contributed substantially to the mainstream of Indian overseas trade and expansion of indian maritime culture. The flourishing ports and the enterprise of Kalinga merchants played a leading role in overseas activities for economic progress and for political and cultural interactions. The maritime traditions of the Odias have been preserved in the legends and cultural institutions of the present day Orissa. The Tapoi festival,Khudarkuni Osha and Boita Bandana of Kartika Purnima are commemorative traditions of ancient Kalingan maritime heritage.

Reference

Behera,K.S.,(1992),”Glimpses of the Maritime Activities of Kalinga”,Orissa Review,,Bhubaneswar,Vol.XLIX, No.IV,p.1-5.

Behera,K.S.,(1994),”Maritime Contacts of Orissa-Literary and Archaeological Evidence”,Utkala Historical Research Journal,Vol.V,Bhubaneswar.

Behera,K.S.,(1999),ed.Maritime Heritage of India,New Delhi.

Behera,S.C.,(1982), Rise and Fall of the Sailodbhavas,Calcutta,p.13-24.

Dash,Kailash Chandra,(1999),”Dantapura and Puspagiri”,Journal of Orissan History,Vol.IX,p.1-15.

Dash,Kailash Chandra,(1999),”Apheterion of Periplus”,Studies in India`s Maritime Trade Through the Ages,ed.Amitabh Mukherji,Institute of Historical Studies,Calcutta.

Dash,Kailash Chandra,(2001), “Odisara Nauvanijya”(in Oriya),Bahitra(Chandbali Pujya Puja Sansad),Chandabali,p.19-21.

Dowson,John,(1867) The History of India as told by its Historians,Vol.I, Trubner and Co.,London,p.5-6.

Kara Birupakshya, (1931),”Maritime Activities in the Ancient Utkala”,The Prachi,Vol.I,part-II,p.1-32,Cuttack.

Panda,Radha Charan,(1934),”Chilikara Prachina Abastha”(in Oriya),Sahakara(Oriya Monthly Magazine),Vol.15,No.3,p.219.

Pattnaik,A.P.,(1988),”Bismrita,Bilupta Chelitalo Bandara”(in Oriya),The Sambad,Sunday,17th July,Bhubaneswar.

Pradhan,Devraj,(1991),”Manikapatna:Ancient Port City on Chilka”,Kalingas,The Brave,Souvenir,Bhubaneswar.

Roy,Satindra Narayana,(1932),”The Sea in the Folklore of Orissa”,The Prachi,Vol.II,No.I,p.49-73,Cuttack.

Rajaguru,S.N.,(1992),Inscriptions of the Temples of Puri and Origin of Sri Purusottama Jagannatha,Vol.I,Sri Vihar,Puri.

Ray,H.P.,(1997),”Orissa in the Chinese Historical Records”,The Utkala Pradipa,ed.K.S.Behera,Vol.I,No.I,Bhubaneswar.

Mukherji,B.N.,(1981),”The Relevance of the Periplus to the Hisotry of Orissa”,Journal of the Orissa Research Society,Vol.I,Bhubaneswar.

Singh,Jagabandhu,(1929/1964),Prachina Utkala,Bhubaneswar.

Shasmal,Narayana,(1946),”Prachina Utkalara Nauvanijya”(in Oriya),Nabeen(Oriya Weekly from Brahmapur),Ist October.

Sarkar,H.B.,(1986),Trade and Commercial Activities of Southern India in the Malayo-Indonesian World,Vol.I,Calcutta.

Sinha,B.K.,(1999),”Maritime Activities of the Kalingas and the New Light thrown by the Excavations at Khalkatapatna”,Maritime Heritage of India,ed.K.S.Behera,p.172-178,New Delhi.

Thapar,Romila,(1983),Ashoka and the Decline of the Mauryas,New Delhi.

Tripathy, Narayana,(1930),”Kharavela and the Madalapanji”,Journal of Bihar Orissa Research Society,Vol.XVI,p.211-215.

Tripati Sila,(2000),Maritime Archaeology,Historical Descriptions of the Seafarings of the Kalingas,new Delhi.

Watters,T.,(1973),On Yuan Chwang`s Travels in India,Vol.I and II,new Delhi.