Pradeep Kumar Panda

Odisha has been among the pioneers of using Public Financial Management (PFM) practices for advancing gender equality and socio-economic development of children. Over the years, Odisha has been a model state for women and child welfare measures among all India states.

In its Budget for 2019-20, the Odisha government has introduced two detailed fiscal statements—gender budgeting and child budgeting. These policy tools help create fiscal space for providing a framework to integrate “social content” of the macro policies. These attempts are truly “public policy innovations”.

At present, many countries have started to publish gender and child budgets. But, a major chunk of these initiatives across countries are just confined to the national level. As far back as 1999-2000, the Department of Women and Child Development, Government of India, had recognised the significance of a “gender lens” in the budgetary processes and had commissioned a study of the same to the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Later, in collaboration with NIPFP, and with the acceptance of recommendations of the ministry of finance’s Committee on “Classification of Budgetary Transactions” under the chairmanship of the then chief economic advisor Ashok Lahiri, India began gender budgeting in FY06. India has, thus, around 15 years of gender budgeting at national level, with gender budget statements published within the Expenditure Budget (Volume 1). Later, in 2008, the Union government released the first child budget statement.

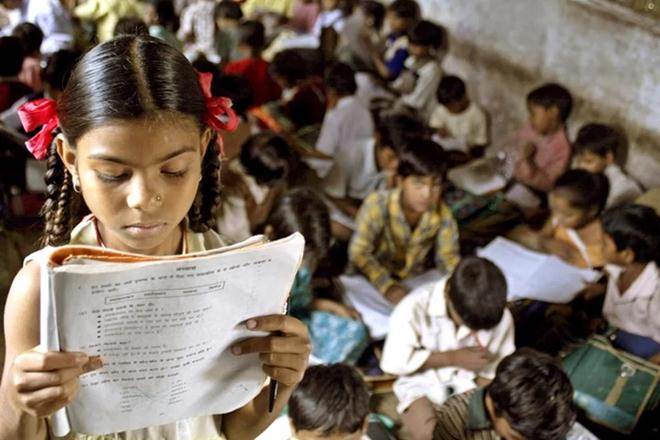

In India, these fiscal innovations are essential at the national and subnational levels, especially since the country is home to every fifth young child in the world. However, the commitments at the state levels to conduct both gender and child budgeting have been quite uneven and have broadly lacked political sustainability. Against this backdrop, Odisha’s efforts to publish the two PFM-related statements in FY20 Budget are indeed commendable.

Odisha witnessed a real GSDP growth rate of 8.35% in FY19, exceeding the all-India growth rate of 7.2% in FY19. The state has also been constantly making efforts to reduce socio-economic disparities related to gender, protect children from poverty by protecting their rights, providing education and better health facilities. Around 27% of the state’s children are under 15 years of age.

Although, some of the child-related indicators, especially IMR (Infant Mortality Rate)—the probability of a baby dying before his/her first birthday—has reduced from 65 to 40 deaths per 1,000 live births as per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) data, the story does not end here. The need for a defined child budgeting came from the alarming figures of NFHS-4 at the “disaggregated levels”.

As per the survey, IMR is much higher for children in rural areas vis-a-vis urban areas. It is also highly correlated with the level of education of mothers. Mothers with 10 or more years of schooling have experienced a lower IMR (18 per 1,000 live births) as compared to mothers with typically no schooling (58 per 1,000 live births). Under-five mortality is also high for rural areas (52 deaths per 1,000 live births) as compared to 24 deaths per 1,000 live births in urban areas.

Although there has been improvement in the nutritional status of the children since NFHS-3, anthropometric indicators have not shown any substantial change. As compared to NFHS-3, the percentage of children who are stunted (45% to 34%) and underweight (41% to 34%) have shown significant improvement. But, there has not been much change in wasting. Child malnutrition is still a persistent problem in the state of Odisha.

This diagnosis makes it compelling for Odisha to introduce child budgeting. Such policy imperatives have also gotten attention after the National Action Plan on Children (2017) based on four objectives—survival, health and nutrition, education and development, protection and participation.

Odisha’s child budgeting—prepared by the Odisha finance department in collaboration with UNICEF—is indicative of the spending that directly or largely affects the children in the age-group of 0-18 years, and is defined on four grounds: Development, Health, Protection and Education. The methodology used by the Odisha government has been consistent with the gender budgeting of the Government of India following NIPFP methodology.

Odisha has identified ten departments for child budgeting. The child budget estimates show the school & mass education, and the women & child development departments get the maximum share of the total Odisha budget for FY20. Broadly, the total child-related expenditure constitutes around 16% of the total budget of the state, and stands at 4% of total GSDP of the state for FY20.

With regard to gender budgeting, Odisha has identified 13 departments that spend directly (100%) on gender-specific interventions while the state has listed 29 departments that see at least 30% share of their total budget go for gender-specific allocations. The estimates showed that conclusively, gender-specific interventions form 8.6% of GSDP while if we consider only 100% specifically targeted programmes for women, they are just 0.45% of GSDP for FY20.

However, both documents—the gender budget and child budget—are silent on fiscal marksmanship. Fiscal marksmanship denotes the fiscal forecast errors. It shows the deviation between what is budgeted and what is the actual spend/revenue across sectors. Higher budgetary allocation per se does not guarantee higher spending.

Odisha’s efforts to use Gender Budget and Child Budget as tools of budget transparency and accountability are laudable.

(The author is a New Delhi based Economist)